Old Quebec is bound to the sea by the St. Lawrence River and four centuries of trade at the gateway to a continent.

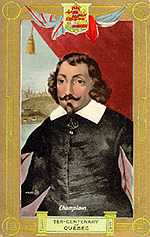

In 1608, French explorer Samuel de Champlain built a fort and storehouse here, adopting its Algonquin name kebec, meaning place where the river narrows. The settlement was the early hub of Canada’s fur industry and the capital of France’s colonial empire in North America.

Control of the fur trade in North America was a source of constant rivalry between French and English colonists. A series of wars between these groups and their Indigenous allies led to the British capture of Quebec City in 1759.

In 1763, France gave Canada and all French territory east of the Mississippi River to Britain. Quebec was made into a British stronghold. Furs, timber and fish now flowed to London.

For more than 100 years Quebec prospered as a bustling maritime city. It was the cradle of great fortunes and a port of entry for millions of immigrants fleeing hardship and injustice in the Old World. Among them came thousands of Anglophones who made their lives in Quebec.

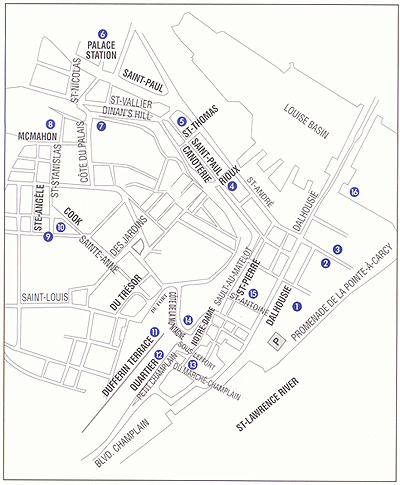

This Heritage Trail walking tour leads to monuments and points of interest that recall Quebec’s heyday as a major naval centre in the 19th century — a time when English communities played a vital role in the city’s life.

GETTING THERE

If you come by automobile, head for the Old Port district in Lower Town by following signs for Boulevard Champlain, which runs along the river beneath the cliff. The road becomes rue Dalhousie. Park in any of the pay-parking lots along the riverfront.

POINTE-À-CARCY PROMENADE

POINTE-À-CARCY PROMENADE

Start your exploration of Quebec’s maritime heritage on the Old Port promenade overlooking the St. Lawrence. For 150 years, this shore was the landing site for European ships laden with supplies and settlers bound for New France. In June 1759 an English fleet of 250 warships and 8,000 troops under General James Wolfe laid siege to the French settlement.

Cannonballs and firebombs pounded the town. On the night of September 12, 5,000 British troops sneaked to shore and scaled the cliff leading to the Plains of Abraham, west of the city. French defence forces under General Montcalm were defeated the next morning and Quebec surrendered September 18.

The river then flowed much closer to the cliff than it does today. As wood exports from Quebec grew, timber yards and private wharves sprang up along the shore to accomodate the trade. Much of today’s waterfront is built on reclaimed land.

Quebec’s first deep-water wharf, built in 1817 by the celebrated shipbuilder John Goudie, lay at the foot of rue Saint-Antoine. The site is now partly occupied by rue Dalhousie and an adjacent parking lot. During the War of 1812-14, Goudie and his crew of Quebec artisans earned fame by rebuilding Britain’s fleet of warships at Kingston on Lake Ontario.

CUSTOMS HOUSE

CUSTOMS HOUSE

150 rue Dalhousie

The grand greystone edifice with columns is the Customs House, built in 1851. The customs office, which dates to 1762, was one of the first British civic institutions in Quebec. Its location here greatly favoured Quebec’s development.

Britain’s colonies in North America were given a boost by the Napoleonic Wars. In 1796, Napoleon cut off Britain’s timber supplies in the Baltic region. Britain looked to her new colony for vital ship-building material. Wood soon overtook furs as Quebec’s main export.

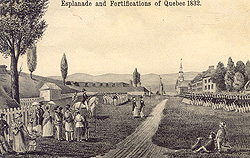

Annual port traffic in Quebec grew from about 100 ships a year in the 1790s to more than 650 vessels in 1810 and 2,000 in 1830.

TRINITY HOUSE (Quebec Port Authority)

150 rue Dalhousie

Trinity House was established in 1805 to maintain order at the growing port. Quebec was then the upstream limit of sailing navigation for ocean-going ships. Each spring when the ice thawed, wood destined for British shipyards was floated down the St. Lawrence in great rafts for transport overseas.

During the shipping season all manner of boats big and small plied the waters. Fishing sloops, tugboats, barges, horse-drawn ferries, rowboats, canoes and river steamers jostled the shores alongside great timber ships.

During the shipping season all manner of boats big and small plied the waters. Fishing sloops, tugboats, barges, horse-drawn ferries, rowboats, canoes and river steamers jostled the shores alongside great timber ships.

For decades, Trinity House wardens regulated all this traffic. They issued pilot’s licenses, looked after lights and buoys in the St. Lawrence and dealt with criminal matters.

In 1858, many of these duties were transferred to the Quebec Harbour Commission. Today this body is called the Quebec Port Authority. The present building next to the Customs House, erected in 1913-14, occupies the former site of the Great Northern grain elevator, razed by fire.

Admire its prominent clock tower, then cross rue Dalhousie and walk up rue Saint-André.

OLD PORT OF QUEBEC

INTERPRETATION CENTRE

100 rue Saint-André

Phone (418) 648-3300

The modern three-storey museum at the corner of Rioux and Saint-André streets shows the history of Quebec City’s Old Port, classified as a National Historic Site. It overlooks a large man-made harbour lined with wharves and docks known as Louise Basin.

The spot on which you are standing was once occupied by beaches, mudflats and a profusion of wharves that stuck out into the St. Charles river. Merchants and boatbuilders dredged the estuary to accommodate their vessels. Over time, enough land was reclaimed from the mudflats to double the surface area of Lower Town. Both Saint André and Saint Paul streets were created this way.

In 1877, with larger steel ships replacing sailing vessels, the Quebec Harbour Commission began a massive dredging project to deepen the harbour. The Princess Louise Basin, named for a daughter of Queen Victoria, was completed in 1890. Construction of the piers was carried out by Irish-Canadian builder John O’Neil.

BELL AND TAYLOR SHIPYARDS

BELL AND TAYLOR SHIPYARDS

Corner of rue de la Canotèrie and rue Saint-Thomas

From the Maritime Museum, head north to rue Saint-Thomas, turn left and walk two blocks to Côte de la Canotèrie. During the early days of the fur trade, this road led to a landing spot for canoes on the shore of St. Charles River.

Scottish entrepreneur John Bell operated a large shipyard just west of rue Saint-Thomas from 1810 to 1836. East of his property lay George Taylor’s shipyard. Taylor, an Englishmen, went into business with his son-in-law Alison Davie here in 1825. Five years later Davie moved across the St. Lawrence to Lévis Point, just north of the ferry terminal. Davie Shipyard remains in business today, the oldest continuously operating shipyard in North America.

A plaque at the corner of rue Saint-Thomas and Côte de la Canotèrie marks the spot where Benedict Arnold was wounded in November 1775 during an attempt by American forces to capture Quebec.

Now return to rue Saint-Paul and turn left, walking west past the Old Port Market to rue Saint-Nicholas.

PALACE STATION

450 rue de la Gare du Palais

Quebec’s shipbuilding heritage dates back to the French regime. From 1739 onward, while still a French colony, Quebec’s Royal Shipyard was located on the St. Charles River near the Intendant’s Palace.

Part of this site is now occupied by the old Canadian Pacific railway station. Built in 1915, the station was designed in the French Château style by architect Edward Prindle. After the Conquest, shipbuilding resumed briefly on the St. Charles River before being interrupted by the American Revolution. Because British law barred merchants from buying U.S. - made boats, many Scottish shipbuilders moved to Quebec for work.

Among the first to build in the 1780s and 1790s were the brothers William, Patrick and John Beatson, who had previously served as officers on fur-trading vessels. They were followed by John and Alexander Munn, John Goudie, William Russell, George Black, Charles Wood and Thomas Menzies, among others.

Quebec shipyards turned out 1,600 wooden sailing vessels between 1763 and 1893 to meet the demand of Britain’s merchant navy. At its zenith in the 1860s, the city’s shipbuilding industry was rivaled in British North America only by Saint John, N.B. At various times, the shipyards employed thousands of artisans and labourers drawn from Quebec’s mixed French-Canadian, Irish, Scottish and English communities. Many of these shipyards and the people they employed were established in the neighbourhood of Saint-Roch, north of Palace Station. It was at his Saint-Roch shipyard in 1818 that John Goudie built Canada’s first steam-powered sawmill.

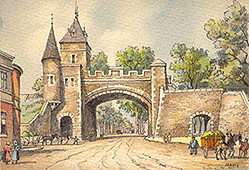

Now climb rue Saint-Thomas toward the Palace Gate entrance to Quebec’s Upper Town district.

DINAN’S HILL

DINAN’S HILL

Note on your left a short street named for Frank Dinan, long-serving alderman in the city and descendant of a prominent Irish family.

Hundreds of thousands of immigrants passed through Quebec in the 19th century, including great numbers of Irish. They accounted for 60 percent of all arrivals from Britain throughout the 1830s; and upwards of 70 per cent during the Potato Famine years 1845-1849. Quebec’s Irish settlers supplied much of the labour on the docks and built many of Quebec’s best-known landmarks.

In 1861, 40 per cent of Quebec City’s 10,000 inhabitants were English-speaking, largely because Irish families made up 30 per cent of the total population. Walk through the gate up Côte du Palais (Palace Hill).

ARTILLERY PARK NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

ARTILLERY PARK NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

2, rue d’Auteuil

Telephone: (418) 648-4205

Website: www.parcscanada.gc.ca/Parks/Quebec/artillerie

Quebec City’s unique military and industrial heritage is preserved at this complex of old defence buildings maintained by Parks Canada. In the Arsenal Foundry you can view a remarkable scale model of Quebec City as it looked in 1808. The Dauphine Redoubt, built in 1713 to house French soldiers, stands at the corner of rue McMahon and rue Saint-Stanislas. Once part of a large Irish neighbourhood, the street was named for Father Patrick McMahon, a defender of Irish Catholic rights and founder of Saint-Patrick’s Parish.

Cross McMahon Street and continue south along rue Saint-Stanislas.

QUEBEC LITERARY & HISTORICAL SOCIETY

(Morrin College)

44 rue Chaussée des Ecossais

Telephone (418) 694 9147

Though Anglophones now make up just two percent of Quebec’s total population, most of the city’s old institutional buildings are of English origin. A sense of Quebec’s Victorian society is admirably preserved in this gem of a library in the old English Quarter, on the corner of Saint Stanislas and Cook streets.

Designed by Francois Baillargé and built as a jail in 1809 by John Cannon, the building later belonged to Dr. Joseph Morrin, a Scottish-born mayor of Quebec. According to Morrin’s wishes the building was made into a Presbyterian college affiliated with McGill University when he died, in 1868.

Today the building houses the library of the Quebec Literary and Historical Society. Here visitors will find a wealth of ancient books, archives and assorted memorabilia. Plans are underway to turn an unused portion of the old prison into an interpretation centre honouring Quebec’s Anglophone past.

ST. ANDREW’S CHURCH AND KIRK HALL

5 Cook Street

The small church directly in front of the Literary and Historical Society was designed for Quebec’s Presbyterian community in 1809-1810 by architect John Bryson. The church hall (Kirk Hall) behind it was added in 1836 and served as a school for parishioners’ children.

DUFFERIN TERRACE

DUFFERIN TERRACE

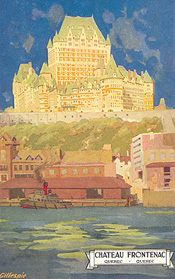

Cook Street turns into rue Sainte-Anne, which leads to Place d’Armes in front of the Château Frontenac and onto Dufferin Terrace, a magnificent 200-foot-high boardwalk overlooking the St. Lawrence. Imagine the excitement here in 1809 when John Molson’s first steamboat, the Accommodation, made its appearance on the water below. Or in 1833, when the Royal William, a wooden ship built at Quebec by James Goudie (son of John Goudie) made naval history by becoming the first steamship ever to cross the Atlantic Ocean.

Now, return to Lower Town by riding the funicular down the cliff.

QUARTIER PETIT CHAMPLAIN

Irish stevedores and their families used to live at the base of the cliff along the narrow street leading to your right. The Petit Champlain district is a busy tourist hub these days, but in the 1800s the street mostly advertised the misery of poverty. To make matters worse, from the 1840s to the 1880s a series of deadly rockslides ravaged the neighbourhood. Canada’s labour movement got its start here in 1857 with the founding of the Quebec Ship Laborers’ Benevolent Society, the country’s first union. The Society protected stevedores from dishonest ship captains and offered financial support to members who’d lost income due to injury or illness.

Stroll past the boutiques, then turn down onto rue Marché Champlain.

OLD LONDON COFFEE HOUSE (Maison Chevalier)

50 rue du Marché-Champlain

Built in 1752, this remarkable crimson-roofed structure was once home to French merchant Jean-Baptiste Chevalier. Sold to an Englishman in 1806, the building became an inn and was known throughout the 1800s as the London Coffee House. Today the the Musée de la Civilisation mounts temporary exhibitions here.

Follow the signs for Place Royale, a market square which is the site of Samuel de Champlain’s original settlement. From here, go to the end of rue Notre Dame and cross Côte de la Montagne.

SITE OF THE NEPTUNE INN

SITE OF THE NEPTUNE INN

Corner of Côte de la Montagne and rue Sault au Matelot.

On this site stood one of the more popular eating and drinking establishments of the early 1800s, the Neptune Inn. According to Irish journalist Edward Allen, who toured Canada with a certain Captain Blake, the Neptune was a favourite haunt of sea captains passing through the port.

Now walk down Côte de la Montagne and turn left on rue Saint-Pierre.

SAINT PETER STREET

(rue Saint-Pierre)

Quebec became one of the world’s busiest port cities thanks to demand for Canadian wood. By 1840, Quebec ranked fifth in the world in terms of trade volume. Lumber barons, shipping magnates and bankers controlled most of the commerce. For many decades rue Saint-Pierre was the financial centre of Lower Canada.

In 1818, John Woolsey opened his Quebec Bank along this street to serve the timber trade. The same year saw the birth of the Quebec Stock Exchange and the opening of a branch of the Bank of Montreal, started by John Molson. At one time, there were four banks at rue Saint-Pierre’s intersection with rue Saint-Jacques.

The Quebec Fire Insurance Co. erected headquarters on rue Saint-Pierre. The British America Assurance Co., the Colonial Life Assurance Co. and State Fire Insurance Co. of London all had offices here.

This concentration of financial institutions earned rue Saint-Pierre fame as the “Wall Street of Quebec.”

Turn right on rue Saint-Paul, cross rue Dalhousie and return to the Pointe à Carcy Promenade along the waterfront.

Naval Museum of Quebec

170, rue Dalhousie

Tel: (418) 694-5387

Website: http://navreshq.queb.dnd.ca/fr/musee.htm

You may wish to end your tour with a visit to Quebec’s Naval Museum. It’s located near the Louise Basin in a modern white building facing the Pointe à Carcy Promenade. The museum details marine history in the region since the beginning of the 20th century. The Battle of the St. Lawrence, a crucial episode of World War II, is a major theme. Admission to the museum is free.

Call ahead for visiting hours.

FURTHER READING

Eileen Reid Marcil’s book, The Charley-Man: A History of Wooden Shipbuilding at Quebec 1763-1893 is an excellent account of this city’s long naval tradition. It’s published in French under the title, On Chantait Charley-Man: La construction de grands voiliers à Québec de 1763 à 1893.

Carraig Books offers a range of publications devoted to Quebec’s Irish heritage, including The Shamrock Trail, a walking-tour guide to Quebec City written by Marianna O’Gallagher. For more information, call (418) 651-5918.

Other Resources

Audio-guided tours of Quebec City are available through the Tourist Centre at 12 rue Saint Anne, across from the Château Frontenac. The $10 fee covers the cost of renting a compact disc and CD player. Call (418) 654-1115 for more information.

The City of Quebec publishes a walking-tour guide to the city’s historic sites called From the Cliff to the Shore which can be obtained from city hall at a cost of $4.

The Heritage Trail series is presented by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network, funded jointly by the Department of Canadian Heritage and Economic Development Canada. Space constraints preclude mention of all possible sites. Many thanks to Marianna O’Gallagher for her help. For more information call the QAHN office at (819) 564-9595 or toll free within Quebec at 1 (877) 964-0409.![]()

![]()