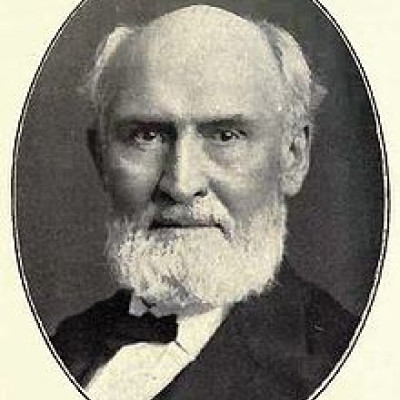

Macdonald College in Ste. Anne de Bellevue is remembered as a bequest of Sir William Christopher Macdonald, and it was a gift of extraordinary generosity. Not only did he perceive the need for an agricultural and teaching college, but he also acquired the land, ordered the design of the buildings, paid the costs of construction and endowed the institution. The college was only one of many gifts from possibly the most generous philanthropist in the history of our country. What do we really know about the man and his own history?

Born the youngest son of Donald McDonald in the colony of Prince Edward Island in 1831, he was of Highland Scots descent. Although his mother was from a prominent Protestant family, his Catholic father insisted that the children be brought up Catholic. In the 1820s and 30s, these religious differences were important. Several of his siblings devoted themselves to the Catholic Church, but William formally rejected his religious heritage in a disagreement with his father when he was sixteen, and his secularism characterized all of his actions thereafter. It would be easy to dismiss this vehemence as just a characteristic of a single-minded, success-driven man, and we cannot know more with any certainty because his personal papers were destroyed when he died. Even so, his family’s religious history sheds some light on what may have driven him.

Born the youngest son of Donald McDonald in the colony of Prince Edward Island in 1831, he was of Highland Scots descent. Although his mother was from a prominent Protestant family, his Catholic father insisted that the children be brought up Catholic. In the 1820s and 30s, these religious differences were important. Several of his siblings devoted themselves to the Catholic Church, but William formally rejected his religious heritage in a disagreement with his father when he was sixteen, and his secularism characterized all of his actions thereafter. It would be easy to dismiss this vehemence as just a characteristic of a single-minded, success-driven man, and we cannot know more with any certainty because his personal papers were destroyed when he died. Even so, his family’s religious history sheds some light on what may have driven him.

Highland chief Alexander M’Donald, head of the Glenaladale branch of Clan MacDonald, stood with Bonnie Prince Charlie when he invaded Scotland in 1745. Prince Charles Stuart attempted to take back the British throne for his father, the Catholic King James and both Catholics and Highlanders, people like M’Donald, suffered reprisals subsequent to their defeat at the battle of Culloden in 1746. For many years after, all Catholics and Highlanders were assumed to have been sympathizers. John MacDonald, the son and heir of Alexander M’Donald and the grandfather of Sir William, grew into his role as chief of the Glenaladale branch with this ever-present burden of his faith. Having been educated in a Catholic seminary in Bavaria, he was a sophisticated, worldly man who spoke 5 languages, and his first loyalty was to the Catholic Highlanders. In 1770, when a landowner of estates in the Hebrides threatened his tenants with expulsion if they refused to renounce their Catholic faith, the Church found a ready champion in John MacDonald. Mortgaging his estates, he acquired a parcel of land on St. John’s Island, later renamed Prince Edward Island. Calling this new estate Glenaladale, he helped Catholic emigrants from Uist in the Hebrides, as well as from his own clan, to settle there. Concerned by the reports of the problems they faced, he followed them a year later. He would spend the balance of his life fighting for his tenants’ rights in the face of a difficult, Protestant-dominated colonial administration, and he is remembered as a great Catholic benefactor and community leader.

When he died on his estate in Tracadie, Prince Edward Island, in 1810, he left a heavily indebted property to his eldest son Donald. Sir William was Donald’s youngest son. Each generation spelled the family name differently for a variety of reasons, and Donald spelled it McDonald. He was by no means a worthy heir to his father’s legacy, and proved to be a mean-spirited landlord. No doubt because of his father’s reputation and the status of his wife’s family, he sat on the Legislative Council. He aggressively promoted landed property rights and was cited as a key figure in an 1841 investigation into trading practices of the elite and again years later as an example of why landlords had to be controlled. In time, he would be manoeuvred out of the Council altogether. When William was only 7, his father was already dealing with overt threats from his tenants to counter his aggressive tactics. In contrast to his own father, the Catholic benefactor, he had developed the reputation of a tyrant, going so far as to threaten to evict his Catholic tenants in favour of Protestants because he felt a local priest was organizing them into a tenants’ union. At 16, William and his father had a major falling out, the consequence of which was William’s renunciation of religion and the beginning of his own business career. He left PEI at 18, as his father’s problems worsened.

On an early July morning in 1850, arsonists burned four vacant buildings belonging to Donald McDonald, and soon he was living with armed guards as other buildings were threatened. The written record conveys the impression that he was a very tense and angry man with a short fuse, keeping those around him perpetually on edge. In his favour, though, Prince Edward Island was rife with tenant/landlord problems at that time, and McDonald was among the few who actually lived in the colony. Most landowners resided in England and choked the local economy from a distance. In fact, the problems were so serious that they would play an important role in encouraging PEI to join in Confederation in 1871.

One evening in August, a month after the fires, while McDonald was standing in the dusk on his back porch, one of his own guards shot him, presumably thinking he was an intruder. He recovered from buckshot wounds to the head, arm and legs, but there seems to have been little sympathy for him among his tenants. The following July a more blatant attempt was made on his life. He was shot early one morning when leaving for Charlottetown and left bleeding where he fell on the road. The gunshots had come from two directions, suggesting a planned attempt on his life. No one would touch his bleeding body for some time, but finally one of his tenants loaded him onto a wagon and carted him to the hospital in Charlottetown. It is rumoured that the good Samaritan was so severely pilloried for saving McDonald’s life that he had to leave PEI altogether. While a reward was posted for information leading to the gunmen, it was later concluded that McDonald was always armed and would not have hesitated to shoot to kill on his own account. The case was not pursued, but reference was made to it when his status on the Legislative Council was reviewed.

Matters with his family ran no more smoothly. He had differences with his brother and his mother and was estranged from several of his own children.

While William experienced some setbacks after leaving his father’s home, he and one of his brothers moved eventually to Montreal where they proved themselves as importers. He did not reconcile with his father until 1854, when the elder McDonald visited Montreal. Impressed with William’s business acumen, he decided to sell his holdings in PEI and move to Montreal, but he contracted cholera shortly afterwards and died in Quebec City.

Sir William was an introspective man, and while it is clear that his formative years were coloured by the temperament of his father, he remained close to his mother and respectful of his siblings. He worked with his brother Augustine, and they were successful importers of tobacco products and edible oil merchants in Montreal from 1854 to 1866. It has been suggested that they capitalized shrewdly on the American Civil War by importing such things as tobacco from the Confederate south into Montreal and then selling them back into the northern Union states. This gave them a solid financial backing for the next stages of their lives. In 1866, they dissolved their partnership and William set up a tobacco plant near the harbour in Montreal.

The growth of the company was rapid, and within five years he had over 500 employees, and five years later he built a new factory that was the largest in his field in Canada. His success is attributed to his tight management style and his belief in quality. He employed few middle management staff, keeping himself closer to the product, and relied on its reputation, eschewing advertising and credit. The formula worked, and by 1895 he is said to have been the biggest taxpayer in the country, but there was one peculiar contradiction in his personality. While he prided himself on his knowledge and judgement of tobacco leaf, he did not use the stuff, or even like it, and was ashamed of making money peddling it to people who did.

William Macdonald never married and only one of his six siblings did. His elder brother married late in life, to a girl less than half his age, and had nine children, assuring the genetic succession. William helped them in many ways, contributing to the children’s education. A few years after his brother’s marriage, in 1868, William invited his mother and one of his sisters to live with him in Montreal, and thus lived in a household rather than in a hotel for the first time since leaving his childhood home. His sister had become a Protestant, and this seems to have been acceptable to Macdonald, who would probably not have invited them had she been a practising Catholic. Their household was situated near McGill College, a factor that was to have an unforeseen consequence.

William Macdonald met John William Dawson, Principal of McGill College, one day on the McGill campus. Dawson, eleven years his senior, also hailed from the Maritimes, and the two men became fast friends. They both had a love of learning and believed in the importance of education. The records show that Macdonald’s first gift to the school, a sum of $1,750 for biological equipment, was made in 1869. In 1871, Dawson participated in a survey of Prince Edward Island and published his Report on the geological structure and mineral resources of Prince Edward Island. That same year Macdonald made a second gift, this time of $5,000, to the college.

There is not a lot of information about their friendship, but Macdonald continued to support the college, mostly the sciences. He gave whole buildings, underwrote the costs of some department Chairs, and gave grants to other departments. His gifts amounted to $13,000,000 to the college and its successor university over his lifetime. That sum, adjusted for inflation from 1905, would be in excess of $280,000,000 in today’s currency—and McGill was not the only beneficiary of his largesse.

Casual observers crossing Canada today might assume that the name Macdonald is just so commonplace that it is a coincidence that it recurs in many different places—or they might assume that we have frequently honoured our first prime minister, Sir John A. MacDonald. The truth is more astonishing. Sir William Macdonald did not give money blindly but targeted his gifts to areas where he was satisfied that they would create a lasting benefit or help a cause that he deemed worthy. He had a particular interest in rural schooling, probably harkening back to his own youth, and among the projects he funded were the Macdonald Manual Training Fund and the Macdonald Consolidated Schools Project. His funding and encouragement helped schools right across eastern Canada, and he is credited with initiatives that led to the creation of both the University of Victoria and the University of British Columbia. He contributed funding to the Women’s Institute movement that evolved into the Macdonald Institute of Home Economics at Guelph University, and contributed Macdonald Hall, an exclusively female residence that opened there in 1904. Buildings and programmes carry his name throughout the country. Macdonald eventually turned the running of the company over to his very reliable right-hand man, David Stewart. He concentrated on his projects, arguably as a way of atoning for having made money through the sale of tobacco. He did not seem to respect people for buying or needing tobacco, and since he did not use it himself, he may have felt he was playing on other people’s weaknesses. He was a complex man who had wanted to pursue a higher education in his youth, perhaps the crux of the disagreement with his father when he was sixteen. His father and two elder brothers had been educated at Stonyhurst College, a Jesuit-run boarding school in England, but he was sent to Charlottetown’s Central Academy. Perhaps his father had run too short of money to send another son overseas, or perhaps he was not judged to be academic material. Whatever their disagreement, it seems to have touched on religion and education, and these two subjects remained with Macdonald for his whole life. After both his mother and sister had died, he invited his niece, Anna, to come and take care of his household. About five years later, in 1894, she became engaged to a Catholic member of the clan, a man named Alain Chartier McDonald. Her uncle expressed his wish that she not marry him. All that is recorded is that he said “I do not wish it.” When she proceeded to marry anyway, he cut his relatives out of his life—and ultimately out of his will. It is speculation to suggest that he objected to the marriage on a religious basis, but it seems indicated.

Sir William Macdonald received a knighthood in 1898 in recognition of his philanthropies in education, and it was only then that he changed the spelling of his name from McDonald to Macdonald. In 1914, he became Chancellor of McGill University, and that same year David Stewart fell seriously ill. Macdonald passed away three years later, leaving his company to two of David Stewart’s sons. He also left large sums to Macdonald College, the McGill Faculty of Medicine, and to the Montreal General Hospital. The Stewart sons carried on with the same community spirit as Macdonald had always shown. It was only under their management that Macdonald Tobacco started making cigarettes, and during the Second World War, when the government obliged tobacco companies to send cigarettes to the troops, Macdonald Tobacco demonstrated its civic responsibility by sending the best quality. When the war ended and the troops returned, their brand rose to the top of the market. The brothers also established the Macdonald-Stewart Foundation that still carries on the philanthropic work of Sir William Macdonald, supporting innumerable initiatives in education and the arts in communities across Canada.

In 1905 Macdonald conceived of the idea of Macdonald College, and two years later, in 1907, it officially opened. The 2007 Annual General Meeting of the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network is an opportunity to celebrate this centennial at the Macdonald Campus of McGill University, the current name of his college.

Principal sources: Dictionary of Canadian Biography, -Stanley Brice Frost, Robert H. Michel, F.L. Pigot and Ian Ross Robertson; Macdonald Museum, Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia; McGill University; Stonyhurst College; University of Guelph; Audrey Paré; westegg.com inflation calculator; Canadian Encyclopedia

Pull Quotes:

“At 16, William and his father had a major falling out, the consequence of which was William’s renunciation of religion and the beginning of his own business career.”

“While he prided himself on his knowledge and judgement of tobacco leaf, he did not use the stuff, or even like it, and was ashamed of making money peddling it to people who did.”

“Sir William Macdonald did not give money blindly but targeted his gifts to areas where he was satisfied that they would create a lasting benefit or help a cause that he deemed worthy. He had a particular interest in rural schooling, probably harkening back to his own youth…”