--October 8, 2015.

The following is the first installment in a series written by Sandra Stock, as part of QAHN's project, Housewife Heroines: Anglophone Women at Home in Montreal during World War II, which has been funded through the Department of Canadian Heritage's World War Commemorations Community Fund.

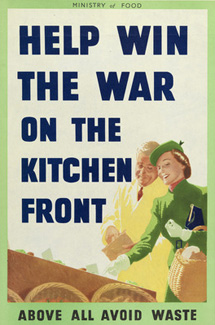

One of the main issues for any country involved in warfare is feeding both its troops and its civilians. The production, harvesting, processing and, especially, the transportation and delivery of foodstuffs becomes an essential undertaking. During the Second World War, Canada was (as it still is today) a major exporter of surplus foods – grains, meat and dairy, in particular – and war, of course, disrupts this important aspect of trade. During the war as never before, women in Montreal households were faced with obtaining and preparing healthy and, if possible, appealing, meals for their families.

One of the main issues for any country involved in warfare is feeding both its troops and its civilians. The production, harvesting, processing and, especially, the transportation and delivery of foodstuffs becomes an essential undertaking. During the Second World War, Canada was (as it still is today) a major exporter of surplus foods – grains, meat and dairy, in particular – and war, of course, disrupts this important aspect of trade. During the war as never before, women in Montreal households were faced with obtaining and preparing healthy and, if possible, appealing, meals for their families.

In many ways, the 1930s were a transition period for domestic life. By this decade, Montreal, Canada's largest city and industrial centre, had a greater variety of food available than previously. There were now refrigerator cars on trains and the iceman delivered regularly (although the ice box did not to give way to home refrigerators until after the war). There were also regular deliveries of bread and milk. This freed up the housewife from daily shopping. The local milkman with his horse would remain a neighbourhood fixture in residential areas such as Notre Dame de Grâce well into the 1950s.

Most shopping was done either at large markets like Atwater or Jacques Cartier Square, with farmers bringing in produce from the countryside, as had been done for centuries and, in some cases, on the same locations as markets of the French regime. There were also small stores that specialized in meat, fish, or fruit and vegetables. These were positioned on commercial streets close to residential districts. Sherbrooke Street West, between Girouard and Grand, was an example of this. The stores were close together but nothing like the supermarkets that would follow after the war, and that, sadly, put most of them out of business.

The housewife headed out at least two days a week – Tuesdays and Fridays seemed to be favoured – and she usually dressed up for the occasion – in a dress, hat and, except in very hot weather, gloves. All of these stores delivered; the housewife would scan the goods and place her order. This routine was nearly universal, since by then, even the very rich had few servants any more, and most people did their own shopping. The act of getting out of the house probably added to a growing sense of freedom among women, and it certainly had a strong social side – meeting the neighbours, chatting with the grocer, and so on. This system hung on into the 1950s, along with the milkman and his horse.

The housewife headed out at least two days a week – Tuesdays and Fridays seemed to be favoured – and she usually dressed up for the occasion – in a dress, hat and, except in very hot weather, gloves. All of these stores delivered; the housewife would scan the goods and place her order. This routine was nearly universal, since by then, even the very rich had few servants any more, and most people did their own shopping. The act of getting out of the house probably added to a growing sense of freedom among women, and it certainly had a strong social side – meeting the neighbours, chatting with the grocer, and so on. This system hung on into the 1950s, along with the milkman and his horse.

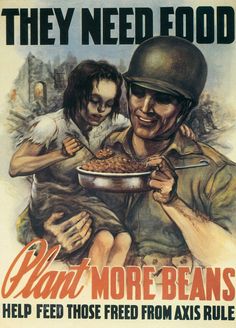

A note on fish: Montreal was thoroughly Roman Catholic, so the government push to have Montrealers eat more fish, at least on Fridays, was not a problem here. Surprisingly, lobster was not considered the gourmet item it is now. It was seen as a “junk fish” and not eaten much until the Canadian Department of Agriculture started promoting it with such statements as, “It's Patriotic and Pleasant to Eat Canadian Lobster.” Apples were also touted as patriotic food.

The reasons behind this emphasis on local products was that, as Ian Mosby has said, “Early in the war, Canadians were asked to contribute voluntarily to Canada's food export commitments by avoiding foods that were needed in Britain and by consuming more Canadian foods whose European export markets had disappeared, therefore threatening farmers and fishermen with unused surpluses...” So, lobster cocktail, lobster à la king and lobster sandwiches became the choice dishes.

Recipes and recipe books became prevalent as never before during the war years. Food production, nutrition and conservation were hot topics both on the radio and in print. This was the flowering time of the home economist radio. Kate Aitken was the best known of the home economists, writing for The Montreal Standard and heard on Montreal radio stations. There were other food experts, such as Chatelaine magazine's Helen Campbell, and even fictional women like the Vancouver Sun's “Edith Adams.” These wartime avatars all had attractive alliterative names of British origin and comforting personas like a favourite aunt. As dated as they may seem to us now, these female food and home economy experts, both real and fictional, probably did more than many people to assist the Canadian housewife dealing with shortages, ration books and absent family members. They also, somewhat unintentionally, opened the non-print media world to women.

A recipe: The Canadian War Cake

A recipe: The Canadian War Cake

This is mixed in a pan on top of the stove. It has no eggs or butter and uses brown sugar, not white.

Two cups of brown sugar.

Two cups hot water.

Two tablespoons of lard.

One pound of raisins.

One teaspoon of salt, one teaspoon of cinnamon, one teaspoon of cloves.

Boil for 5 minutes after the mixtures starts to bubble. When cooled off, add one teaspoon of soda (Baking soda) dissolved in hot water.

Add three cups of flour.

Bake this mixture in two loaf tins for 45 minutes in a slow oven. (A slow oven is usually around 250 to 325 degrees F.).

(In Part II - We'll look at rationing and victory gardens and another recipe)

Sources:

Ian Mosby, Food on the Home Front during the Second World War

http://wartimecanada.ca/essay/eating/food-home-front-during-second-worl…

Recipe – www.canada.com/home-front