October 19, 2015.

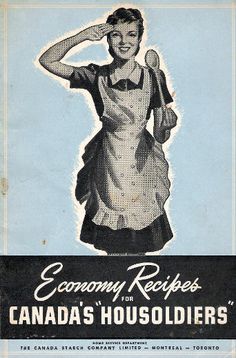

The following is the first instalment in a series written by Sandra Stock, as part of QAHN's project, Housewife Heroines: Anglophone Women at Home in Montreal during World War II, which has been funded through the World War Commemorations Community Fund.

In wartime, our Montreal home cook has always had to plan ahead and consider that there may be days when she might not be able to go out to the stores. Montreal's severe winters, added to the general apprehension about what the future could hold during the war, forced her to find ways to preserve food for the unpredictable times to come. With hindsight 70 years later, we know that Canada emerged economically well off and that the Allies won, but, of course, a Montreal housewife and her family didn't know that back in 1939. She also couldn't know when the war would end. Communications were limited compared to what we have today. The media were also much more controlled by the government that they are today. Radio was still in its infancy and newspapers couldn't penetrate wartime censorship. It was a slower world.

In wartime, our Montreal home cook has always had to plan ahead and consider that there may be days when she might not be able to go out to the stores. Montreal's severe winters, added to the general apprehension about what the future could hold during the war, forced her to find ways to preserve food for the unpredictable times to come. With hindsight 70 years later, we know that Canada emerged economically well off and that the Allies won, but, of course, a Montreal housewife and her family didn't know that back in 1939. She also couldn't know when the war would end. Communications were limited compared to what we have today. The media were also much more controlled by the government that they are today. Radio was still in its infancy and newspapers couldn't penetrate wartime censorship. It was a slower world.

So, all those carrots, cucumbers, tomatoes, apples and peaches from our ubiquitous victory gardens had to be preserved and put by to last through the winter to supplement what was available through rationing. Potatoes and root vegetables, and apples, could be kept in cool, dry cellars, often packed in clean sand, or even in cooler cupboards or unused rooms against exterior walls. Houses were not as airtight as they are now; most were rather draughty and heated unevenly by coal furnaces that heated hot water radiators. Some homes relied on wood stoves, especially in some of the older or poorer parts of Montreal. There were also small upright wood-burning stoves called Quebec heaters. A house could have several of these, placed in pretty well any room and attached to a stovepipe. Fireplaces were quite small in most Montreal houses of the period and not used for heating except in emergencies. After the war, many Quebec heaters left Montreal for second-home country houses as affluence and travel returned to middle class families. Apartment dwellers relied on larger hot-water heating systems that originated in basement coal furnaces.

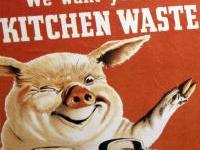

Canning was by far the most popular method of food preservation during World War II. According to Ian Moseby, “From early in the war, the Department of Agriculture promoted home canning through public demonstrations by staff home economists as well as through a range of pamphlets and brochures... Canadians responded with a similar level of enthusiasm to the Department of National War Services fats and bones collection campaign.”

Fats and bones were used in the manufacturing of munitions. The bones provided material for use in industrial glue and fats supplied glycerin for making bullets and cannon shells. Millions of pounds of fats and bones were collected across Canada. At that time, meat products were generally much fatter than what we are used to now. Fat was not seen as an enemy to health but rather fancied. Lard, which is animal fat, was used in cooking and baking rather than the vegetable shortening and even the butter which took over in our diets in the 1950s. Scrap metal, rubber, glass and other items we would now call recyclables were also collected and re-adapted for use by wartime industries. There were more of these articles around then as, for example, glass jars and metal tins (tin!) were used rather than the ever-present plastics of today.

Fats and bones were used in the manufacturing of munitions. The bones provided material for use in industrial glue and fats supplied glycerin for making bullets and cannon shells. Millions of pounds of fats and bones were collected across Canada. At that time, meat products were generally much fatter than what we are used to now. Fat was not seen as an enemy to health but rather fancied. Lard, which is animal fat, was used in cooking and baking rather than the vegetable shortening and even the butter which took over in our diets in the 1950s. Scrap metal, rubber, glass and other items we would now call recyclables were also collected and re-adapted for use by wartime industries. There were more of these articles around then as, for example, glass jars and metal tins (tin!) were used rather than the ever-present plastics of today.

This collecting activity is vividly described by William Weintraub in City Unique, Montreal Days and Nights in the 1940s and '50s: “...housewives were busy responding to the demands of frequent salvage drives. Household waste of every kind was wanted to feed the war machine. Old pots and pans could be melted down to make tanks and guns.”

Youth groups like the Boy Scouts would go from house to house collecting. Everything from old fur coats, to used toothpaste tubes, to old hot water bottles was gathered up and re-purposed. Although some of these items may have had, in reality, little actual re-use value, the morale building and community cohesiveness brought about by the collecting drives themselves probably had a positive effect on the population.

Our recipe: Baked Cereal Pudding and Left-over Porridge

This is from the very popular Five Roses: A Guide to Good Cooking, published in 1938, when war loomed. This Canadian cookbook was produced “under the supervision of Jean Brodie,” another of the home economics ladies who presided over Canadian households at the time.

Two cups of cooked Five Roses Cereal (porridge/oatmeal), one teaspoon of vanilla, two cups of milk, half a cup of sugar, two eggs, one can of sliced peaches, and one cup of puffed raisins.

Add vanilla and milk to the hot cooking cereal. Beat the egg yolks slightly with the sugar and combine with cereal mixture. Drain peaches and reserve the juice for sauce. Place peaches and raisins in greased baking dish, cover with the cereal and egg mixture. Bake in a moderate oven at 350 degrees F. for about 40 minutes. Make a meringue of the two egg whites and three tablespoons of sugar. Pile it on the pudding and return to oven until slightly brown.

Left-over porridge may be added to muffin or pancake batters, to steamed pudding mixtures, and to yeast bread doughs and quick bread batters. If the left-over porridge is stiff, add a little hot water to it and beat well with a fork. It can also be added to the soup kettle. It thickens the soup and adds to the nutriment of the dish.

Sources:

Ian Mosby, Food on the Home Front during the Second World War

http://wartimecanada.ca/essay/eating/food-home-front-during-second-worl…

William Weintraub, City Unique: Montreal Days and Nights in the 1940s and '50s, Toronto, 2004.

Recipe – Five Roses A Guide to Good Cooking, complied by the makers of Five Roses Flour, Lake of the Woods Publishing Company Limited, Montreal & Winnipeg, 1938.