In the lovely windswept high places of early 19th century Dunham, among old-growth forests and newly ploughed fields, where the earliest beginnings of tender apple shoots were beginning to take root, a sinister and corrupt enterprise thrived and threatened to destroy the placidity of the newly settled pastoral community. For the first thirty years or so of its history, Dunham was the centre of counterfeiting in Missisquoi County and in North America as a whole.

In the lovely windswept high places of early 19th century Dunham, among old-growth forests and newly ploughed fields, where the earliest beginnings of tender apple shoots were beginning to take root, a sinister and corrupt enterprise thrived and threatened to destroy the placidity of the newly settled pastoral community. For the first thirty years or so of its history, Dunham was the centre of counterfeiting in Missisquoi County and in North America as a whole.

Catherine Day, a historian of the Eastern Townships, wrote in the 19th century that the American Revolution brought “numbers of worthy and desirable inhabitants” while at the same time “others came in, who could only be regarded in the light of unavoidable evils, being of that irresponsible ill-regulated class who neither feared God nor regarded man.”

Catherine Day, a historian of the Eastern Townships, wrote in the 19th century that the American Revolution brought “numbers of worthy and desirable inhabitants” while at the same time “others came in, who could only be regarded in the light of unavoidable evils, being of that irresponsible ill-regulated class who neither feared God nor regarded man.”

In geographic terms, the Eastern Townships at the end of the 18th century represented Vermont’s last frontier. The artificial boundary that was established in 1783 was largely ignored by the inhabitants of northern Vermont and the region was seen as an economic, social and linguistic appendage of New England.

Government officials on the Quebec side of the border failed to consider how closely Vermont and the Townships shared the natural environment and water routes, language and customs. There was great concern that Americans hostile to Britain would settle in Missisquoi and that settlers, if ever called upon, would not be keen to take up arms against former friends and family members. The region became a place of dispute between French, British and American interests resulting in different markets and legal systems, an uncontrolled financial and banking system, and little legal recourse and law enforcement.

In addition to the political jostling, the Townships were largely unexplored and inaccessible by road. Besides his “thousand inconveniences,” a persistent complaint of the Reverend Charles Caleb Cotton in his letters to his family in England was Cotton’s inability to move through the “hideous wilderness” from one community to another with relative ease. His efforts to travel to major centres such as St John’s or Montreal in order to find some familiar comforts of home were always thwarted by hardships along the way. His descriptions of roads and travel were usually punctuated with phrases such as “long and tedious” or “inconvenient and difficult.” As late as the 1830s, a survey of the roads near the border succinctly described them as “very rugged, broken and otherwise bad”.

In addition to the political jostling, the Townships were largely unexplored and inaccessible by road. Besides his “thousand inconveniences,” a persistent complaint of the Reverend Charles Caleb Cotton in his letters to his family in England was Cotton’s inability to move through the “hideous wilderness” from one community to another with relative ease. His efforts to travel to major centres such as St John’s or Montreal in order to find some familiar comforts of home were always thwarted by hardships along the way. His descriptions of roads and travel were usually punctuated with phrases such as “long and tedious” or “inconvenient and difficult.” As late as the 1830s, a survey of the roads near the border succinctly described them as “very rugged, broken and otherwise bad”.

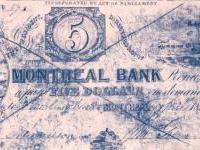

The Jacob Ruiter papers of 1803, held in the National Archives in Ottawa, include a petition that was presented to the Governor from the magistrates, militia officers and inhabitants of the Seigneury of St. Armand concerning the disruption of tranquility by “unprincipled men” who have commenced the practice of counterfeiting bills of different banks in the United States. “Since that year,” Ruiter said, “the counterfeiters have become exceedingly numerous inasmuch that a gang of them is established in almost every one of the newly settled Townships and emboldened by impunity, they have openly proceeded to the commission of every species of villainy and fraud […] and they are daily emigrating thereto to spend in drunkenness and riot the gains of their iniquity.” Philip Ruiter noted that “they crowd at the most public places and by their idleness and debauchery corrupt the morals of the young and old of both sexes and produce incalculable injury to the community.” The petition, which asked for a change in the law “to produce the remedy of the disorder complained of,” apparently fell on deaf ears not just then but for years to come.

Philip Ruiter (1765-1820) was an accomplished Loyalist and well known in Missisquoi County as a Justice of the Peace and a Commissioner for the Trial of Small Causes. In his store ledger of 1808-1836, Ruiter recorded legal cases that he heard in his position as Justice of the Peace. Perhaps Ruiter’s most interesting entry concerned the conviction of William Babcock for making counterfeit American currency. Ruiter stated that this was a “subtle craft to deceive” and charged William Babcock as a “rogue and a vagabond” and sent him to the house of correction in Philipsburg for two months. In the conviction record of William Babcock, Rumabout Mandigo is identified as an accomplice of the accused and he too was sentenced to the prison for his part in the deceit.

Philip Ruiter (1765-1820) was an accomplished Loyalist and well known in Missisquoi County as a Justice of the Peace and a Commissioner for the Trial of Small Causes. In his store ledger of 1808-1836, Ruiter recorded legal cases that he heard in his position as Justice of the Peace. Perhaps Ruiter’s most interesting entry concerned the conviction of William Babcock for making counterfeit American currency. Ruiter stated that this was a “subtle craft to deceive” and charged William Babcock as a “rogue and a vagabond” and sent him to the house of correction in Philipsburg for two months. In the conviction record of William Babcock, Rumabout Mandigo is identified as an accomplice of the accused and he too was sentenced to the prison for his part in the deceit.

In 1819, the Reverend Fitch Reed (1796-1871), a Methodist Episcopal circuit minister from New York, stated: “I was told that every family in Cogniac Street was concerned in the production of spurious bank bills. These bills are purported to be on the banks in the United States; the Canadian authorities troubling themselves but little about the matter, so long as their own bills were not counterfeited.”

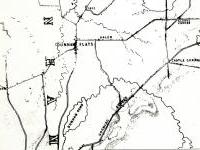

The 1839 “Gore map” of Dunham indicates a tiny road that meandered up into the hills. Both on the map as well as in the secret counterfeiting circles this dirt road was referred to as Cogniac Street. The road still exists but now bears the name “chemin Hudon.”

The 1839 “Gore map” of Dunham indicates a tiny road that meandered up into the hills. Both on the map as well as in the secret counterfeiting circles this dirt road was referred to as Cogniac Street. The road still exists but now bears the name “chemin Hudon.”

The counterfeiters developed their own slang terms for their profession and their stock and trade. We no longer call a counterfeiter a “coniacker,” yet the term was once in such wide circulation that it was included in an 1859 compendium of slang. The word “coniacker” itself may be rooted from other old words such as “cog” which meant to cheat or swindle and “cony” which was a victim of a swindler. Counterfeit money was also called “cony,” “French horses,” “snags” or “boodles.”

The counterfeiting business was under the direction of three competing gangs. Seneca Paige was a savvy businessman from Vermont and led the Dunham counterfeiters throughout much of the 1820s and 1830s. In partnership with him, and yet controlling a large enterprise of its own, was the Gleason family.

Ebenezer Gleason Sr. was an illiterate farmer with a cunning mind for business who helped to build an international network of dealers for Seneca Paige. His son, Ebenezer Gleason Jr., worked in Philadelphia as an agent for Cogniac Street. A similar collective had also formed around the Turner Wing family which was in partnership with a skilled copperplate engraver named William Crane. For over twenty years, the companies fought for the greater share of the market of counterfeit notes. Although the Wing Company operated a profitable business, it was Seneca Paige who assumed the leadership role and under his direction, Cogniac Street became the leading supplier of counterfeit money throughout the United States. By the 1830s, an extensive network of wholesalers, distributors and dealers looked to Paige to supply them with money.

Ebenezer Gleason Sr. was an illiterate farmer with a cunning mind for business who helped to build an international network of dealers for Seneca Paige. His son, Ebenezer Gleason Jr., worked in Philadelphia as an agent for Cogniac Street. A similar collective had also formed around the Turner Wing family which was in partnership with a skilled copperplate engraver named William Crane. For over twenty years, the companies fought for the greater share of the market of counterfeit notes. Although the Wing Company operated a profitable business, it was Seneca Paige who assumed the leadership role and under his direction, Cogniac Street became the leading supplier of counterfeit money throughout the United States. By the 1830s, an extensive network of wholesalers, distributors and dealers looked to Paige to supply them with money.

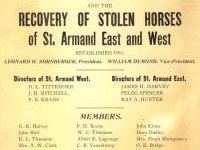

Dealers who visited Cogniac Street purchased notes in a variety of ways. Payment could be in cash (based on current rates) or in goods such as watches and jewellery. Stolen horses, however, became the most common currency. Horses were portable and served to move the currency as well. Gangs of horse thieves doubled in the 1820s and 1830s, so Cogniac Street was not only the centre of counterfeiting but the centre of horse thieving, as well. To counteract the rise of this activity, communities founded Horse Thieving Societies to track down the thieves and the horses.

To be continued...