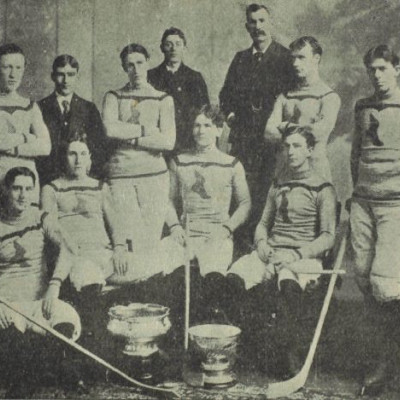

Led by the brilliant Hall of Famers Harry Trihey and Arthur Farrell, the Montreal Shamrocks, also known as the “Fighting Irish,” were an Irish Catholic hockey club that revolutionized the sport on their way to winning two Stanley Cups in 1899 and 1900. Formed out of the old Montreal Crystals Hockey Club in 1895, the Shamrocks were owned by the Shamrock Amateur Athletic Association, which also operated the legendary Shamrocks Lacrosse Club. The lacrosse club played its games where Marché Jean-Talon exists today (there is still a rue Shamrock behind the market), whereas the hockey club, like all of Montreal’s élite-level teams (the Shamrocks, Victorias, and Montreal Hockey Club, affiliated with the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association), played at the Montreal Arena. The Arena stood at the corner of Sainte-Catherine and Wood in Westmount, where Place Alexis-Nihon stands today.

The Arena was one of the first indoor arenas designed exclusively for hockey, after ones in Manhattan and Ottawa, and opened for the 1898 season. Unlike other hockey arenas, which had square corners, the Montreal Arena had rounded end boards, which allowed the puck to be ricocheted around the ends of the rink, speeding up the game. The Arena seated 4,300 spectators, though capacity could be increased to up to 10,000 for big games. It also had concessions to offer patrons food and drink. The Arena was also home to the first artificial ice-making machine in North America, installed for the 1915 season. The Montreal Canadiens called the Arena home from 1911 until it burned down in 1918. (The Habs began play at the Jubilee Arena, at the corner of Sainte-Catherine and Moreau in the east end, where they moved back to after the Montreal Arena burned down. The Jubilee also burned down, in 1920, forcing the Habs to move to the Mont-Royal Arena at the corner of Mont-Royal and Saint-Urbain, where they played until the Forum opened in 1924).

The Arena was one of the first indoor arenas designed exclusively for hockey, after ones in Manhattan and Ottawa, and opened for the 1898 season. Unlike other hockey arenas, which had square corners, the Montreal Arena had rounded end boards, which allowed the puck to be ricocheted around the ends of the rink, speeding up the game. The Arena seated 4,300 spectators, though capacity could be increased to up to 10,000 for big games. It also had concessions to offer patrons food and drink. The Arena was also home to the first artificial ice-making machine in North America, installed for the 1915 season. The Montreal Canadiens called the Arena home from 1911 until it burned down in 1918. (The Habs began play at the Jubilee Arena, at the corner of Sainte-Catherine and Moreau in the east end, where they moved back to after the Montreal Arena burned down. The Jubilee also burned down, in 1920, forcing the Habs to move to the Mont-Royal Arena at the corner of Mont-Royal and Saint-Urbain, where they played until the Forum opened in 1924).

Prior to the end of the first decade of the 20th century, élite-level hockey players were not professionals. The top level clubs in Montreal, Ottawa, and Quebec were comprised of young men, most of whom were still students at the classical colleges and universities. The first hockey game was played at the Victoria Arena (located on what is today blvd. René-Lévesque between Drummond and Stanley streets where a parking lot now stands across from the Bell Centre) on March 3, 1875, between two teams comprised of members of the Victoria Skating Club and students from McGill. Following this first game, until the late 19th century, hockey was an exclusively Anglophone sport. Indeed, in terms of hockey, it was the Irish who bridged the gap between Anglo-Protestants and French Canadians. Montreal’s Irish Catholics shared two classical Jesuit colleges (Collège Sainte-Marie and Collège Mont-Saint-Louis) with the French Canadians; instruction was bilingual. This arrangement ended in 1896 when the Irish established Loyola College (now part of Concordia University). At Collèges Sainte-Marie and Mont-Saint-Louis, the Irish introduced the sport to their French Canadian classmates and co-religionists. The Shamrocks were also the first élite-level Anglophone club to have Francophones on it in the middle of the first decade of the 20th century.

Like any expansion team, the Shamrocks struggled through their first few season in the Canadian Amateur Hockey League (CAHL). Over the 8-game schedule in 1896-98, the Shamrocks won all of 5 games, dropping the other 19, and being outscored 103-68. The 1898 season, however, was the turning point. After going 1-7 in 1896 and 1897, Trihey, Farrell, and the others who would go on to win the Cup, joined the club. That year, the Shamrocks were a respectable 3-5, finishing 3rd in a five-team league (the Montreal Hockey Club, the Victorias, Quebec, and Ottawa were the other clubs).

It was during this season that Trihey, the captain, began to tinker with ideas for speeding up the game, and gaining an advantage over the Shamrocks’ opponents. In this era, hockey, like rugby today, was a game of off-sides, and forward passing was illegal. To get around this, most teams simply had their pointmen (or defencemen) chip the puck into the opponents’ zone for the forwards to chase down; in other words, they forechecked. Trihey came up with a new idea: he and the other three forwards (hockey was a seven-man game then) rushed out of the defensive zone together, in close quarters, carrying the puck up the ice with a series of quick sideways and backwards passes, skating in and around the opposing defence. This allowed the Shamrocks to maintain possession of the puck and avoid a forecheck in their own zone, enabling them to get into scoring positions in the offensive zone.

In 1899, Trihey’s innovations began to pay off, as the Shamrocks went 7-1 (the only blemish was a season-opening loss to Ottawa). The Shamrocks finished first in the Canadian Amateur Hockey League (CAHL) that season, and won the Stanley Cup for their efforts (the Cup went to the CAHL regular-season champion). Trihey potted 19 goals in the 7 games he played (the next closest player in the goal-scoring race was Clare McKerrow of the Montreal HC, with 12). Ten of Trihey’s goals that season came in a single game against Quebec on February 4 in a 13-4 rout of Quebec.

Though the CAHL regular season champion was declared the winner of the Stanley Cup, the champions of the other leagues around the country could challenge the CAHL champion for the Cup. On March 14, 1899, only 10 days after winning the Cup, the Shamrocks were challenged by Queen’s University. The game ended in a rout for the Shamrocks, 6-2. The Queen’s challenge also saw some incipient trash-talking from its captain, Curtis, who, after the loss, complained about the refereeing, the ice, and the length of the Shamrocks’ sticks. Curtis also opined that the general quality of play in Ontario was lower than that of Quebec and had his club been playing in the Quebec league, it would have “easily won out” against the Shamrocks.

In the 1900 season, the Shamrocks defended their league title, going 7-1 again, losing the last game of the year, 4-3, to Quebec. Trihey again led the league in scoring, this time with 17 goals in 7 games. The Shamrocks were declared the winners of the Stanley Cup for the 2nd straight year. During the CAHL season, the Shamrocks were challenged by the Winnipeg Victorias for the Cup. A best-of-three series was played at the Montreal Arena in February. Unlike the Queen’s University team, the Winnipeggers were a serious cup contender, having wrested it away from the Montreal Hockey Club in an 1896 challenge.

Coverage of the 1900 challenge series in The Gazette bordered on the hysterical. When Winnipeg shocked the Shamrocks and took game 1 by a 4-3 score, the newspaper was devastated, but had to admit the Winnipeg side deserved the win. However, when the Shamrocks stormed back to take the next two games, The Gazette was beside itself. Following game 2, a 3-2 Shamrock victory, it said:

The same exciting features characterizing the first contest were re-enacted. The hockey was sensation in its perfection. Intense excitement prevailed throughout. The final ten minutes, with Shamrock leading by one point and their western opponents straining every resources of nerve and sinew in desperation of pulling down the vital margin, developed the wildest demonstration. The cheering of ten thousand throats was deafening.

When the Shamrocks took the series 2 games to 1 with a 5-4 victory on February 16, The Gazette chortled that “The Stanley Cup Likes Not Western Weather.”

Following the challenge series with Winnipeg, the next challenge could only be a disappointment for hockey fans, as the Halifax Crescents, the champions of the Maritime league, issued one. The Crescents travelled to Montreal in March 1900 for a 2-game series at the Arena. This one wasn’t even close as the Shamrocks romped to 10-2 and 11-0 victories, with Farrell scoring 8 of his team’s 21 goals, Trihey chipped in with 5 of his own.

This was the end of the Shamrocks’ dynasty, however. The following season, 1901, saw them return to mediocrity with a 4-4 record, to finish 3rd in the 5-team league. Before the season ended, however, the Winnipeg Victorias were back in Montreal, attempting to wrest control of the Cup away from the Shamrocks. This time, they were successful, sweeping a best-of-3 series in 2 games. The second game of the series, after Winnipeg won the first game 4-3, was the first overtime game in Stanley Cup history before the Victorias’ captain, Don Bain, scored after 4 minutes to win the game 2-1. Following the end of the 1901 season, the majority of the Shamrocks’ stars, including Trihey, Farrell, and goalie Frank McKenna, hung up their skates.

Many of the Cup-winning Shamrocks went on to enter the bourgeoisie of Montreal in the early 20th century. Trihey became a prominent lawyer, with offices on what was then called Great St. James Street (rue Saint-Jacques now) in the old city and a home in Westmount. When World War I came about, Trihey was front and centre in the Irish community of the city, helping to organise the Irish-Canadian Rangers, a unit in the Canadian militia. When an overseas boundary was formed to fight in France, beginning in 1916, Trihey was made the commanding officer.

The British had initially promised the Rangers that they could fight together as a single unit on the frontlines. After they arrived in Britain, however, command changed its mind and the Rangers were broken up, to be fed into the frontline as reinforcements as needed. Trihey was furious and resigned his commission in disgust. He returned to Montreal and penned a scathing letter to the editor to the New York Post during a visit to Manhattan. The letter, which was equal in its scathing attack on the British and Canadian military bureaucracies, was incendiary in Canada after it was republished in both French and English in Montreal newspapers. The Canadian military authorities in Ottawa thought it to be seditious and moved to prosecute Trihey. Fortunately for Trihey, however, he had friends in high places, including the Minister of Justice, Charles J. Doherty, who intervened to prevent charges from being filed against him.

Following his retirement, Arthur Farrell entered his father’s merchant business. During his playing days, when he was at the peak of his fame in 1899, he had authored a book on hockey strategy. Following his retirement, he wrote at least two more, including one in the prestigious and influential series of sporting books by the Spalding Company of New York City. Unfortunately for Farrell, however, he died young of tuberculosis at a sanatorium in the Laurentian town of Sainte-Agathe-des-Monts, one day before his 32nd birthday in 1909.

As for the club itself, the Shamrocks fell on hard times following the 1901 season. They never again had a winning season, stumbling along until 1910. After the 1910 season, and a 2-10 record in the East Coast Hockey Association, the successor to the CAHL, the Shamrocks folded. They were done in by declining revenues and professionalization. They simply could not afford the élite players anymore. At the same time, élite-level professional and amateur hockey in Canada, from 1908 until the creation of the National Hockey League in 1917, was rife with factionalism, feuds, and strife, as leagues were formed, disbanded, and reformed to keep some teams in, some teams out.