It was mid-November and the sky overhead was a brilliant shade of blue when we arrived at the Sherbrooke home of our guide for the day, Isabell MacArthur Beattie. Isabell, a second-generation Scottish Canadian who learned to speak Gaelic as a child in her home in the high country around Milan, had agreed to show us around the old Scottish settlements in that out of the way part of the country. It was only later in the day that I would learn (to my surprise) that Isabell was actually a great-grandmother and in better shape than many people half her age. Indeed, as we trudged across fields and through forests that day in search of long-lost Scottish history, we had to be careful not to lag too far behind our guide. And by the end of the day, as we visited yet another Scottish burial ground, Isabell said “this has been great exercise.” I told her that I couldn’t agree more, and that we could not have found a better guide!

It was mid-November and the sky overhead was a brilliant shade of blue when we arrived at the Sherbrooke home of our guide for the day, Isabell MacArthur Beattie. Isabell, a second-generation Scottish Canadian who learned to speak Gaelic as a child in her home in the high country around Milan, had agreed to show us around the old Scottish settlements in that out of the way part of the country. It was only later in the day that I would learn (to my surprise) that Isabell was actually a great-grandmother and in better shape than many people half her age. Indeed, as we trudged across fields and through forests that day in search of long-lost Scottish history, we had to be careful not to lag too far behind our guide. And by the end of the day, as we visited yet another Scottish burial ground, Isabell said “this has been great exercise.” I told her that I couldn’t agree more, and that we could not have found a better guide!

So first thing that bright Monday morning, I set out for Scottish country with my colleague, Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network (QAHN) executive director Dwane Wilkin, Isabell and her husband Ross. Taking Route 108, we passed through Birchton and Cookshire on our way to Gould, home to a rather commercial “Scottish festival” in recent years.

Gould, our guide explained, was one of the first areas settled by the Scots in the Eastern Townships. The origins of the village, and the Township of Lingwick that surrounds it, date back to 1838 when the first poverty-stricken Scots from the Isle of Lewis arrived in the area. They settled on lands owned by the British American Land Company, and most of them arrived with little more than the clothes on their backs.

Gould, our guide explained, was one of the first areas settled by the Scots in the Eastern Townships. The origins of the village, and the Township of Lingwick that surrounds it, date back to 1838 when the first poverty-stricken Scots from the Isle of Lewis arrived in the area. They settled on lands owned by the British American Land Company, and most of them arrived with little more than the clothes on their backs.

Yet, by all accounts, the country these people came to was a lot more appealing than the one they left behind. Back home, they had been restricted to tiny parcels of land (crofts) for which they had to pay rents – usually in kind -- to their landlords. Their lot had been one of extreme poverty, and their lives had been based on a perennial dependence on potatoes, fish and seaweed. Further waves of Scottish immigration to the Eastern Townships were encouraged by a disturbing trend in Scotland known as the Clearances.

The Clearances involved the forced eviction of crofters from their lands to make way for sheep. Sheep were deemed more profitable, especially when tenants were behind in their rents. Making life even more unbearable for the crofters were failures in the potato crop. So hundreds of families immigrated to the Townships, settling on lands purchased from the British American Land Company. Life was hard -- immigrants were obliged not only to pay for their land, but also to clear it of trees and build roads -- but at least there was hope. In time, many Scots turned from farming to logging to make their living.

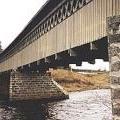

Today, little remains of Gould. There’s a general store, a United Church and a sprawling graveyard filled with stones bearing the names of early Scottish settlers. A short distance out of town is the McVetty-McKerry covered bridge, the longest bridge of its type in the Townships, and named for the Scottish craftsmen who built it in 1893.

A few years ago, Isabell was involved in an initiative of the Presbyterian Church of Canada. The plan was to erect a monument to the early Scottish Presbyterian churches in the area. Since the first Scottish settlers arrived here in the 1830s, with a congregation organized in 1845, Gould was deemed an appropriate location for the monument. “But the municipality turned us down; they wouldn’t even speak to us. They said that the history of Gould began with the creation of the French Catholic Parish [i.e., Sainte-Marguerite-de-Lingwick] in 1908, and that nothing existed before that. Of course, we know our own history a bit better than that!”

A few years ago, Isabell was involved in an initiative of the Presbyterian Church of Canada. The plan was to erect a monument to the early Scottish Presbyterian churches in the area. Since the first Scottish settlers arrived here in the 1830s, with a congregation organized in 1845, Gould was deemed an appropriate location for the monument. “But the municipality turned us down; they wouldn’t even speak to us. They said that the history of Gould began with the creation of the French Catholic Parish [i.e., Sainte-Marguerite-de-Lingwick] in 1908, and that nothing existed before that. Of course, we know our own history a bit better than that!”

A short distance beyond Gould, we passed through Sainte-Marguerite. We used to call this ‘the French village,’” Isabell explained. Further up the highway, to our surprise we noticed that the fields and hillsides were covered in snow. “Does it always snow this early?” I asked. “Oh yes, this is typical,” Isabell explained. “We are up quite high in this part of the Townships, and the snow arrives early.” I remembered that as we travel east we head into the Notre-Dame Mountains. At 1,105 metres, Mount Megantic is the highest peak in this range.

We eventually passed a dirt road named Tolsta Road. Tolsta, one of numerous Scottish settlements in this part of the country, took its name from a village on the Isle of Lewis, where most of the settlers came from. A little further up the highway, just past a farmhouse, we noticed a large archway over a cart track leading into a pasture. The sign read “ Tolsta Cemetery.” In the distance we could see gravestones encircled by a fence. Opening the gate and trudging across the snowy field, we came to an isolated but well kept burial ground with several dozen gravestones. The oldest stone dated to 1851. Cows were grazing in the distance. “So this is what’s left of Tolsta,” I thought.

Returning to the car, we continued on to Stornoway, where we stopped at the Winslow Cemetery, a beautifully kept burial ground in the centre of the village. Maintained by the Lewis Cemetery Association (named after the Isle of Lewis and formed to look after a number of the area’s old Scottish burial grounds), the cemetery occupies a prominent spot across from the Catholic Church. Stornoway itself is situated on the crest of a hill and commands a spectacular view of the surrounding countryside.

Returning to the car, we continued on to Stornoway, where we stopped at the Winslow Cemetery, a beautifully kept burial ground in the centre of the village. Maintained by the Lewis Cemetery Association (named after the Isle of Lewis and formed to look after a number of the area’s old Scottish burial grounds), the cemetery occupies a prominent spot across from the Catholic Church. Stornoway itself is situated on the crest of a hill and commands a spectacular view of the surrounding countryside.

Isabell showed us a magnificent monument commemorating the early Presbyterian churches of the area – the very same monument originally planned for Gould. The red and black granite monument features a map of the area and histories of the various little churches that served the Scottish communities in Lingwick (Gould), Winslow (Stornoway), Marsboro, Milan, Lake Megantic and Scotstown. The monument tells the story of when these churches were erected and how they declined over time as a result of shifting settlement patterns. Appropriately the text on the monument is in three languages: English, French and Gaelic. “My Gaelic was a bit rusty, so we had to get some help with the grammar,” Beattie laughed. “When we asked permission to put up the monument though, people here were so enthusiastic; it was wonderful.”

Isabell took me to her grandparents’ gravestone. John McArthur and Catherine McDonald, Gaelic Scots from Lewis. Catherine died in 1912; John, age 92, the year after. Strolling about the grounds, we noticed a number of gravestones with inscriptions in Gaelic.

Isabell took me to her grandparents’ gravestone. John McArthur and Catherine McDonald, Gaelic Scots from Lewis. Catherine died in 1912; John, age 92, the year after. Strolling about the grounds, we noticed a number of gravestones with inscriptions in Gaelic.

A mailbox near the monument contained a guest book. It would be the first of several that we would sign over the course of the day.

Located about a kilometre from Stornoway on Route 161 is an old grist mill. Built in 1883 by Télesphore Legendre, the mill operated until about 1940. To avoid icing up during the cold winter months, Legendre placed his mill wheel on the inside. “This was the only grist mill around here,” Isabell explained.

Located about a kilometre from Stornoway on Route 161 is an old grist mill. Built in 1883 by Télesphore Legendre, the mill operated until about 1940. To avoid icing up during the cold winter months, Legendre placed his mill wheel on the inside. “This was the only grist mill around here,” Isabell explained.

“My father would bring our barley and buckwheat here to be ground. Barley was used in Scottish barley scones; we also fed it to the pigs. Buckwheat made good pancakes. We also grew oats, but oats didn’t need to be ground, since they were fed to the horses. I remember my father coming to the mill when I was a child. It was a long trip and he had to stay over night.”

(See On the Trail of the Scots, Part 2)