GASPÉ BAY PIONEER MUSEUM

As with any museum, part of its mandate is to display exhibits of a historical nature. When it was decided that the first project of the pioneer museum would be whaling and whalecraft, it was necessary to conduct research in this area. After much of the research was completed, it seemed like a natural progression that a short publication be writ-ten to accompany the exhibit. I set about this task, and the result is “The Whalers of Gaspé Bay – A Family Perspective” which, I hope, will give the reader a brief overview of the history of whaling in the Gaspé area.

INTRODUCTION

At first glance one may wonder why the title of the booklet on whaling includes the words “a family perspective” in the title. I will attempt to describe a feature of Gaspé Whaling that was not evident to me before I undertook this activity, my family’s involvement.

My Gaspé roots go deep and far as the Boyle family first arrived in Gaspé in 1789. Many speculate that they were Loyalists, which may be the case, though I have found no strong evidence to support this claim. They were in Gaspé at the right time and came from the right place to be considered Loyalists but little is known of their origin. Edith Mills, in her book on her family, “Remembrance,” puts forth three hypotheses of how the Boyles came to be in Gaspé. One states that the Boyle family was granted land in the area for services in the military, another is that members of the family were shipwrecked on the Gaspé Coast and made their homes there, and yet another states that they were Loyalists and received land in Gaspé for this reason.

But what is certain is that they were shipbuilders, mariners and some be whalers. Evidence of this can be found in archives, old letters and texts, etc.

I always knew that my family was involved in whaling, but what I didn’t know was that, not only was it a family enterprise, but an extended family activity as well. It turns out that not only were the Boyle brothers involved in this activity but a brother-in-law was as well. In fact, when I first started researching the family and its activities, It was interesting to see the extent of these interrelations, as the readers will see for themselves.

During my research, It was of interest to note that many Gaspésians did not know of the extent of whaling in the Gaspé and its importance to the com-merce of the time.

It is my purpose, in authoring this text, to give an overview of the whaling industry and the implications of this activity for Gaspé Bay, and I will do this in the context of one family’s involvement in this trade, the Boyles.

So please read on and hopefully you will enjoy the adventure as much as I have.

James F. Caputo

THE WHALING INDUSTRY-OIL FOR OUR LAMPS

Whaling is a very old industry practiced by man since pre-historic times. One of the earliest records of whaling are carved drawings found in Korea which depict Stone Age people hunting whales using boats and spears.

In North America whaling was divided between that of native and the commercial enterprises. Commercial whaling, during the 18th and 19th century, was centered in the United States. New Bedford and Nantucket Island in Massachusetts were two very important centers for this trade.

The industry reached its zenith in 1843 when 729 ships with total crew members of over 20,000 were involved in the trade. In a mere 50 years the whaling trade was almost over.

A few years ago, when conducting research on primitive lighting devices and their uses, I discovered the importance of whale oil as a fuel for these devices. Whale oil burned very cleanly and with little odor, unlike other animal fat or fish oil which could give off a strong odor, particularly that of fish oil.

Besides oil for lamps, other whale products were used, such as baleen for buggy whips, parasol ribs and to stiffen parts of women’s clothing such as in dresses and corsets.

Supply and demand—the use of this oil, of course, brought about a demand for this product and thus the pursuit of the whale for this commodity.

The discovery of petroleum however, was the beginning of the end for the whaling trade. As petroleum products started replacing whale oil for illumination as well as lubricants, the whale industry started to wane considerably.

A WHALING WE WILL GO-THE THRILL OF THE CHASE AND ADVENTURES TO BE HAD

Not only was the whaling trade a lucrative one but it also could be one full of adventure such as the excitement of the hunt and visits to exotic places. These elements of the trade would explain why so many young, as well as those not so young, would follow the whale. What farm boy or merchants son would not like to visit exotic locales and involve themselves in hunting the largest creature on the planet.

Not to say that all was adventure and the thrill of the hunt. There were months of no sighting of their pray, tedious work to perform, monotonous foods - sometimes stale or rancid, to be eaten and sometimes an overbearing captain and treacherous crew to endure.

It could also be dangerous. Many men would fall overboard to be lost at sea. It was surprising the numbers of these sailors who could not swim. Small whale boats could be crushed by the actions of this powerful creature and men could be injured by the implements used to capture and kill the whale. One could be killed in the pursuit of the whale or die from some tropical illness.

THE CHASE

Once a whale was spotted from the larger whaling ship, small boats would set out to pursue and kill their prey. The men in the smaller boats would position themselves within range of the whale to use their harpoons and lances. Harpoons would be driven into the whale by the harpooner, not to kill the whale but to fasten their boat to the whale who, after being tired out, could be killed by the use of long pointed lances. After being harpooned, the whale would usually sound, running deep into the sea. This part of the chase was particularly dangerous for the men of the small boat as the tremendous force of the whale could either capsize the smaller boat, throwing the men into the sea, or smash the boat outright with the same result. Both the harpoons and lances were very sharp and accidental con-tact with these by the whalers could cause serious injury and even death depending on the severity of the injury. If all was successful, the whale would be secured to the small boat and be towed to the larger ship to be processed.

PROCESSING THE WHALE-TRYING OUT

Once the whale had been killed the processing of its blubber (fat) would start. With the use of sharp instruments called spades, the whalers would strip the whale carcas of its outer layer, the blubber, which contained the oil of the animal. These spades were mounted on long spruce poles and would cut the whale blubber from the carcass of the whale into a wide spiral strip.

These large pieces of blubber, called blankets, would be hoisted to the side of the whaling ships and cut into smaller pieces. An instrument called a boarding knife was used to cut the whale blubber (blanket) into more manageable pieces to render the blubber into oil. Once these more manageable pieces were secure, a tool called a mincing knife was used to cut the blubber into even smaller pieces that were then placed into large cast iron try-pots to be further rendered into oil. Some whalers would perform this activity (trying out) aboard the ship but the Gaspe Whalers would usually render the blubber into oil on shore.

THE BEGINNING

Legend has it that the first Gaspé whalers were taught their trade by a man from Nantucket, Massachusetts, who found himself in Gaspé, in the early1800’s. In David Lee’s History of Gaspé, 1760-1867, he states that “Whaling began in Gaspé Bay about the turn of the 19th century; according to tradition, an American from Nantucket instructed the Boyle brothers of Gaspé Bay in his methods of whaling.” I have both read and heard different variations of this story and believe that the recounting of one of them would be interesting to the readers of this text. In “My Father’s Shoes-Our Coffin Story,” the author, Ross Coffin, relates one such story. “Whaling can be credited with bringing the Coffin family to the shores of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and to the area now known as Gaspé. The Government of the day offered bounties to all vessels that brought home a designated amount of whale oil. The cargo had to have been obtained by honest means by the crews of the whalers. The bounty was not to be paid for oil that was not produced from the toil of each ship's crew. To protect the government from deception, an affidavit had to be signed by all crew members upon their arrival home. One such vessel, sailing out of Nantucket, in or about the year 1777, carried two crew by the names of Coffin and Davis, who were cousins. The hunt in the Gulf of St. Lawrence whaling grounds, was not a very successful one, and by the time they were ending their hunt, the hold was half empty. Not having enough whale oil to collect the bounty, and with another whaler within sight, the Captain sought a gam with the other Captain. After some negotiations, the two Captains settled on a price and the whale oil was transferred onto the Nantucket whaler. Shortly after, the Captain asked the crew to swear to the false claim that all whale oil was taken only by the ship's crew. Coffin and Davis had a problem swearing to the false oath, having being of the Quaker faith. The Captain became annoyed with his reluctant crew members and threatened them with abandonment on the nearest shore unless they could come to terms with his lie. Fearing God more than the Captain, Coffin and Davis stood their ground. The Captain ordered the ship to head for shore. Having only the clothes on their backs along with an axe, a muzzle loading gun and three days provisions, the Captain bid them farewell at a place known as Cape Gaspé. Once ashore, the two made their way to Peninsula Point where they set up camp for the night under a very large tree. History would later show that Jacques Cartier camped at the same spot on his first voyage to Canada.

A few days later the two caught the attention of a passing fisherman who took them across the bay to a tiny Gaspé village. After a short time in the village, Coffin set out in a northerly direction along the shoreline where he came upon a large cove. Having the right conditions to start a home, Coffin staked out about a mile of shoreline in which he started his new life. Over time he built a cabin and married a beautiful 16 year old woman named Hannah Ascah. Finding themselves lonely, Coffin soon asked his cousin Davis to come and settle near them. Davis agreed and bought part of Coffin's claim. To the French fishermen, this area was soon named L'Anse aux Cousins or in English, Cove of the Cousins, in recognition of Coffin and Davis, and today the name remains the same.” This story seems plausible as the first Coffin to settle in Gaspé was from Nantucket Island, a major whaling center, and many of the Coffin family were involved in this trade there. Also, the two families were interrelated as Abraham’s son Abraham married the daughter of the first James Boyle, Annabella. Annabella’s brothers, George, John, James and Felix were all involved in the whaling trade.

Records indicate that the Boyle brothers were also ship builder-owners, whalers, and master mariners.

Ship Owners - John, George, and Richard Annett, their brother-in-law, are listed as the owners of the whaling schooner, the Mary Boyle, in 1811. These men, as well as two other Boyle brothers, Felix and James, are also listed as the owners of the whaling schooner, the Annabella, in 1818. Again, in 1828, Felix Boyle is listed as the owner of the whaling schooner Ellen and Jane, probably named after his two sisters.

Ship Builders - These same four Boyle brothers and their brother-in-law, Richard Annett, are listed as the builders of the Mary Boyle - 1811 and the Ellen and Jane - 1825.

Master Mariners –Records indicate that one of the Boyle brothers, Felix, as well as his brother-in-law, William Hall, were both considered to be mas-ter mariners. It should be mentioned that Abraham Coffin is listed as the master of the Good Intent in 1806. Thomas Boyle was listed as a master mariner as well.

Though the focus of this particular text is the Boyle family and their in-volvement in the whaling trade, other Gaspé families were similarly in-volved. Among the other Gaspé Bay Whalers we find the names Adams Annett, Ascah, Baker, Coffin, Miller, Patterson and Tripp.

THE COASTERS AND WHALERS

Many of the schooners built in Gaspé were used for coastal trade, which meant that these vessels were primarily used to carry goods to settlements along the Gaspé coast, to the Maritime Provinces and to Quebec City. They may have gone further but in all probability these vessels were relegated to the smaller geographical area.

In his study “Ship Builders, Whalers and Master Mariners,” the author, David McDougall, states that Gaspé Bay whaling vessels would travel to places such as Kamouraska in the estuary of the St. Lawrence River, around Anticosti Island, through the Straits of Belle Isle, north along the Labrador

coast to the mouth of Hamilton Inlet, south and east throughout the Gulf of St. Lawrence, along the east coast of Newfoundland. In his text he also states that between the years 1853 and 1865 an overall average of 750 barrels of oil were taken per year and adds that the best year was in 1858 when six whaling schooners produced a total of 1624 barrels of whale oil. As stated earlier in this text, the discovery of petroleum soon brought about the decline of the whaling trade which was probably also exacerbated by a decline in the whale population.

THE PREY

Many types of whales were hunted for their oil. The Sperm Whale was especially sought after because of the amount of blubber it had. The Right Whale was slow swimming and easily caught and its thick blubber yielded a great deal of oil.

THE SPERM WHALE

THE RIGHT WHALE

TOOLS OF THE TRADE-WHALE CRAFT

As with any trade, specific tools are needed to carry out the activities of the trade. Below is a brief description of some of these whaling tools or Whalecraft.

WEAPONS OF ATTACK

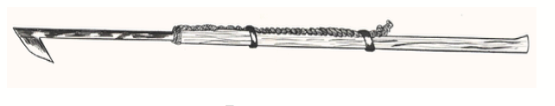

HARPOON

The harpoon was meant to be driven into the whale and afterwards stay attached to the whale. In this

manner the whale would have to pull the whaleboat till tired and at this point the creature could be killed by the use of the lance.

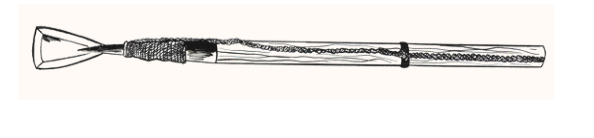

LANCE

When the small whale boat was close enough to the whale the lance would be driven into the whale in

order to kill it.

BOAT SPADE

The boat spade was used to cut the tendons of the whale’s flukes, disabling it.

CUTTING-IN TOOLS

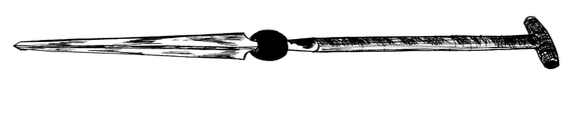

SPADES

These spades were mounted on long spruce poles. They would cut the whale blubber from the carcass

of the whale into a wide spiral strip called a blanket.

BOARDING KNIFE

The boarding knife was used to cut the whale blubber (blanket) into more manageable pieces in rendering the blubber into oil.

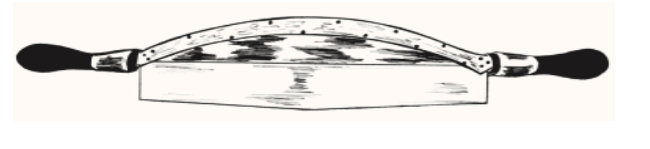

MINCING KNIFE

This tool was used to cut the blubber into small pieces that were then placed into large cast iron trypots to be further rendered into oil.

IN CLOSING

In chronicling the story of the Gaspé Whalers in brief, I hope that I have given the reader an overview of whaling in general and that of the whalers of Gaspé Bay. Also, I hope that I have peaked the inter-est in some who would like to know more about the subject and will avail themselves of the display on whaling lore and implements put together by the Gaspé Bay Pioneer Museum.

This is a beginning of the challenge for me as I plan on doing much more in this regard. In future, I plan on producing a much more comprehensive volume on whaling and hopefully more information on this endeavor as it took place in the Bay will be uncovered.

I especially hope that I have, in some way, encouraged our young to find out more about their forefathers and appreciate the culture and history of early Gaspesians.

Until we meet again and explore this exciting subject together I believe I hear in the distance someone shouting “ther she blows”. I most go and investigate further.

Since this booklets first publication I have found some significant new information regarding this study that should be included in the text. First, unlike the practice of whalers in other locations, the Gaspé Whalers did not render the blubber aboard ship but brought it on-shore to carry out this task. In recent years archeologists from Parks Canada have studied sites on Peninsula point where this rendering practice took place and have indeed found remnants of these activities.

Further I would like to mention that the purpose of my text was to give a family perspective on whaling and should not considered the definitive story. Many more families were involved in this activity in Gaspé, all with their own stories. There is much yet to be written.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Coffin, Ross. “ My Father’s Shoes-Our Coffin Story.” The Island Register.

Doane, Benjamin. Following the Sea, A Young Sailor’s Account of the Sea faring Life in the Mid-1800’s. Halifax: Nimbus Pub- lishing and The Nova Scotia Museum, 1987.

Lee, David. Gaspé, 1760-1867. Canadian Historic Sites, Occasional Papers in Archaeology and History # 23.

Lytle, Thomas. Harpoons and Other Whalecraft. New Bedford: The Old Dartmouth Historical Society Whaling Museum, 1984.

McDougall, David. Ship Builders, Whalers and Master Mariners of Gaspé Bay in the 1800’s. Concordia University, Montreal.

Mills, Edith. Remembrance. 1932.

New Bedford Whaling Museum. Moby Dick and the Tools of Whaling. New Bedford: 1983.

Patterson, Raymond. Family Gatherings Volumes I - III.