This Trail leads to two distinct regions -- Abitibi and Témiscamingue. Together they form Quebec's northwest frontier, and both are still frontier regions today. Ancient home of prehistoric peoples now represented by the Algonquin and James Bay Cree, this vast territory was among the first inland areas of North America to be explored by Europeans and one of the last to be permanently occupied.

In 1686, France and England were locked in bitter war for control of the Canadian fur trade. Rival companies in Hudson's Bay and James Bay had been stealing each other's furs and burning down each other's forts for more than 20 years. Setting out from Montreal, a French expedition led by Chevalier Pierre de Troyes followed the Outaouais River north to roust the English-owned Hudson’s Bay Co.

About 70 Canadiens and 30 French soldiers, including the future founder of Louisiana, Pierre Le Moine d’Iberville, paddled upstream through the forest, stopping to build a makeshift fort at Lake Témiscamingue and then on to Abitibi. Here the south-flowing Outaouais watershed meets the Harricana River, which runs north to James Bay. Abitibi literally means “where the waters part.” A series of ever-larger forts was built where Lake Témiscamingue narrows at Ville-Marie. As exploration and commerce expanded westward over the next century, the Témiscamingue became a gateway to the fur trade.

Lumber merchants rediscovered Quebec’s northern frontier in the 19th century. The town of Témiscaming grew up around the rapids where timber rafts were assembled for the annual log-drive south. By 1880, the first farms had started to appear in the clearings.

The first Abitibi settlers came in 1910 with the arrival of the National Transcontinental Railway. These were railway maintenance crews and their families who were posted every few miles along the track. Loggers began cutting their own homesteads out of the wilderness about the same time. Then, in 1926, the opening of the Horne Mine and Foundry triggered development of Quebec’s leading mining district.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, thousands of poor families from hard-hit urban parishes in the south resettled in the Abitibi as farmers. Some of these pioneers are still alive today.

GETTING THERE

GETTING THERE

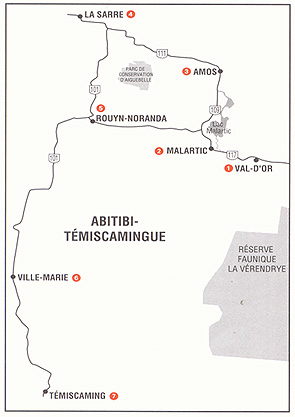

Because of its size and location, be sure to plan at least three days for your exploration of the Trail region. There are two ways to get here by car. From the Trans-Canada Highway at North Bay, Ontario, head north on Ontario Route 63 to the Quebec border at Témiscaming. From Montreal, drive northwest on Autoroute 15 and Route 117 through Saint Jovite, Mont Laurier and the La Vérendrye Wildlife Reserve to Val d'Or. This guide begins at Val d'Or and ends at Témiscamingue, but you can follow the Trail in either direction.

VAL D'OR (pop. 32,130)

Firmly tied to the vagaries of hard-rock mining and world demand for heavy metals, Val d'Or has had many economic ups and downs in its 70-year history. Signs of prosperity and hardship are plain to see.

During boom times, workers flocked to Val d'Or from everywhere. Nowhere is this truer than in the city's spiritual evolution. At various times members of at least 11 faiths have lived and worshipped here: Roman Catholic, Ukrainian Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Anglican, United Church, Presbyterian, Baptist, Pentecostal, Jehovah's Witness, Mormon and Hebrew.

One of the town's earliest mining neighbourhoods remains more or less intact: the Bourlamaque Mining Village. This historic site consists of about 80 modest log homes laid out in neat rows. Built in 1935 to house miners and their families, all but one are still in use as family homes. That one, located at 123 Perrault Street, is open to the public.

From Bourlamaque Village, take Perry and Viney streets to visit the former gold mine its residents once served. La Cité de l'Or has been re-developed as a major tourist site and visitors can tour restored mine facilities both on the surface and at a hundred metres beneath.

Just a few blocks west of here is a small English-language neighbourhood surrounding Golden Valley School, one of three active English schools along the Trail. Watch for English street names here and elsewhere in town: Foley, Fisher, Bacon, Dennison, Johnson, Williston, Wolfe, Nelson, Montgomery, Lawlis, Hammond, Cartman, Forest, Benny.

Another local historic site is the water house of the original Sullivan gold mine, built in 1934 and closed in 1967. It’s located at 456 rue Hotel de Ville.

La Cité de l'Or and Le Village Minier de Bourlamaque

90 Perrault Avenue, Val d'Or.

(819) 825-7616; 1 (877) 582-5367

Website: www.citedelor.qc.ca

MALARTIC (pop. 3,860)

Just 27 km west of Val d'Or, this mining town once had a thriving English-speaking community and school. Few traces remain. The Abitibi-Témiscamingue mineralogy museum here offers a family-oriented look into the fascinating world beneath the Earth's surface.

Musée Minéralogique de l'Abitibi-Témiscamingue

650 rue de la Paix Street

AMOS (pop. 13,380)

AMOS (pop. 13,380)

About 50 kilometres north of Malartic on routes 117 and 109 is the town of Amos. Abitibi's first white settlers arrived here with the National Transcontinental Railway in 1910. The town's centrepiece is the spectacular round-domed cathedral of Sainte Thérèse d'Avila. One of the region's many contradictions can be seen here: the further north one travels north from Val d'Or, the better the farming.

Only 8 kilometres outside Amos, travelers will find La Ferme village, site of a World War I-era internment camp for “foreign aliens.” Most of the 1,200 prisoners housed at Spirit Lake camp were adult male eastern Europeans. Conditions were fairly humane and prisoners were allowed to bring their families if they wished. Labour and diet were similar to conditions in civilian lumber camps that were beginning to pop up in the region. Jean Laflamme’s book, Spirit Lake, Un camp de concentration en Abitibi durant la Grande Guerre, published by Les Editions Maxime, documents this period.

For many years after the war, the La Ferme facilities operated as a school of agriculture. The long-abandoned site is now being restored and redeveloped to receive tourists.

LA SARRE (pop. 8,060)

From Amos, Route 109 heads north through a few more farm villages before entering the untamed James Bay country. Route 111 heads west through the centre of the northern farm belt to the town of La Sarre.

Agriculture came to Abitibi during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Backed by the powerful Roman Catholic Church, the Quebec government convinced -- some say coerced -- thousands of French-Canadian families from poor southern parishes to leave their homes and move north. Entire neighbourhoods were uprooted. Each family was given some bush land and all were expected to clear the land, till the soil, open new parishes and multiply. Various colonization movements continued into the 1950s, pushing further north and eventually exhausting the arable land.

Agriculture came to Abitibi during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Backed by the powerful Roman Catholic Church, the Quebec government convinced -- some say coerced -- thousands of French-Canadian families from poor southern parishes to leave their homes and move north. Entire neighbourhoods were uprooted. Each family was given some bush land and all were expected to clear the land, till the soil, open new parishes and multiply. Various colonization movements continued into the 1950s, pushing further north and eventually exhausting the arable land.

Most of the houses and farm buildings along this route date from the earliest days. Some of the earliest settlers still occupy them, living pioneers.

ROUYN-NORANDA (pop. 41,390)

From La Sarre, Route 101 heads south about 90 kilometres to the twin towns of Rouyn and Noranda. Together they are the heart and soul of Abitibi but they are as different as night and day. Noranda came first, a strictly ordered, English-language company town built around the original Edmund Horne mine and smelter that made Canada's copper capital famous. Rouyn grew up just beyond the town line, home to people who wouldn't or couldn't live the Company line.

Until 1949, the mayor of Noranda was the general manager of Noranda Mines and lived in Toronto. For its first few years, Rouyn did without a mayor at all.

The streets of old Noranda are wide and square and numbered; the rows of houses face each other, the principal buildings face the mill. Here is the town's remaining English school, its curling club and the Dave Keon Arena, named after one of several local hockey greats. Nearby, the narrow streets of Rouyn bend to the landscape at all angles, in all directions.

As in the country, many of the original buildings in both towns are still standing. One of them is now a small museum open by appointment at the Horne Mill, which is also home to the old railway station and several early wooden railway cars.

The Dumulon Historic Store in Old Rouyn is open to the public, as is the Russian Orthodox Church that evokes Noranda's multicultural background.

The local tourism office publishes a 20-site heritage walking tour of Old Noranda.

Rouyn-Noranda municipal website:

www.ville.rouyn-noranda.qc.ca

Dumolon Historic Store

Website: www.maison-dumulon.ca

VILLE MARIE (pop. 2,850)

From Rouyn-Noranda, Route 101 heads south about 100 kilometres to Ville Marie, the oldest town on our trail and northern gateway to the Témiscaming. Strategically located at a narrows near the junction of several major rivers, Ville Marie has been more-or-less continuously occupied by Europeans since the 1690s. At first it served simultaneously as a military outpost and a fur-trading centre, but commerce quickly took over.

Just outside Ville Marie is Fort Témiscamingue National Historic Site. This old trading post has been finely rebuilt by Parks Canada and presents a fascinating portrait of the fur industry from its beginnings through its heyday to the present. The fort also provides a glimpse of Algonquin life before the Europeans came, and a look at the early French explorers.

Fort Témiscamingue National Historic Site

Website: www.temiscamingue.net/fort_temiscamingue

TÉMISCAMING (pop. 3,050)

From Ville Marie, Route 101 heads south about 120 kilometres to the hidden jewel of this region, the beautiful town of Témiscaming. A first sawmill was built in Témiscaming in about 1873. A paper mill followed in 1919. The paper mill's owners, the Riordon Paper Company, carefully planned this spectacular hillside town to lure and keep the best employees. Témiscaming was incorporated in 1921 and famous landscape architect and town planner Thomas Adams was hired. The result was a town of red brick houses and shops in the British style.

In 1930, mill manager C.B. Thorne added the crowning touches. Thorne bought an ornate fountain and Venetian well in Rome and had them shipped home to grace Temiscaming’s main thoroughfare. Dancing bronze figures adorn the Florentine marble well and a statue of Neptune guards the fountain and its ring of lesser Roman gods.

Though Anglophones are very much in the minority today, Temiscaming still maintains its English flavour. The community continues to be served by an English-language school.

This guide is presented by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network. The Heritage Trails series is made possible by grants from the Department of Canadian Heritage and Economic Development Canada. Space constraints preclude mention of all possible sites. For more information, call the QAHN office at (819) 564-9595 or toll-free within Quebec at 1 (877) 964-0409.

![]()

![]()