The conclusion of the American Revolution in 1783 brought forth profound changes to Quebec. The Treaty of Paris negotiated between the United States and Great Britain established the 45th parallel to the south and the span of land to the east, as the boundaries between this part of Quebec and the newly formed republic. In addition to these specific boundary agreements, close to 10,000 displaced persons, wishing to remain loyal to the British Crown chose to immigrate to Canada. Most people migrated into lands west of the seigneuries up river from Montreal, but a small minority of less than 1,000 occupied the Missisquoi Bay area despite government directives that this land was to remain an unsettled buffer zone between the farms of the seigneuries and the United States.

The "Loyalists" who moved into Quebec beginning in 1782 established themselves at the head of Lake Champlain in the vicinity of “Missiskoui Bay” (now Philipsburg). These first settlers were members of the "King’s Loyal Americans,” also known as Jessup’s Rangers or Sir John Johnson’s “King’s Royal Regiment of New York.” Familiar with the shores of the bay from their forays into the region during the American Revolutionary War, these men were resolved to stay in this region despite the fact that it was held as a buffer zone between the American colonies and the seigneuries.

As soon as the presence of these Loyalist refugees became known to the government, they were ordered to relocate. Upon their refusal, their names were removed from aid and provision lists. A steady protest from the Loyalists to the government in the form of petitions and letters flowed from Missisquoi Bay.

The British legislators hoped to avoid a clash of cultures and thus, introduced the Constitutional Act in 1791 which not only divided Quebec into two distinct provinces -- an upriver portion west of Montreal called Upper Canada and the downriver section in the east known as Lower Canada; it also provided the legal framework for two societies in a single state.

The British legislators hoped to avoid a clash of cultures and thus, introduced the Constitutional Act in 1791 which not only divided Quebec into two distinct provinces -- an upriver portion west of Montreal called Upper Canada and the downriver section in the east known as Lower Canada; it also provided the legal framework for two societies in a single state.

On February 7, 1792, the Lieutenant Governor of Lower Canada, Alured Clarke issued a royal proclamation which stated that the crown lands of the province were to be surveyed into townships and the land granted to settlers was to be held according to the British traditions of free-hold land tenure and a Protestant establishment.

Meetings to consider applications for Crown Land and for taking the Oaths of Allegiance were held at Missisquoi bay from 1792 until 1797. In each proposed township, the petitioners formed a Group of Associates under a leader. The first grant which gave each petitioner 200 acres was awarded in 1796 to Thomas Dunn for the Township of Dunham. It was that specific proclamation which initiated the division of the area that would later be known as the Eastern Townships.

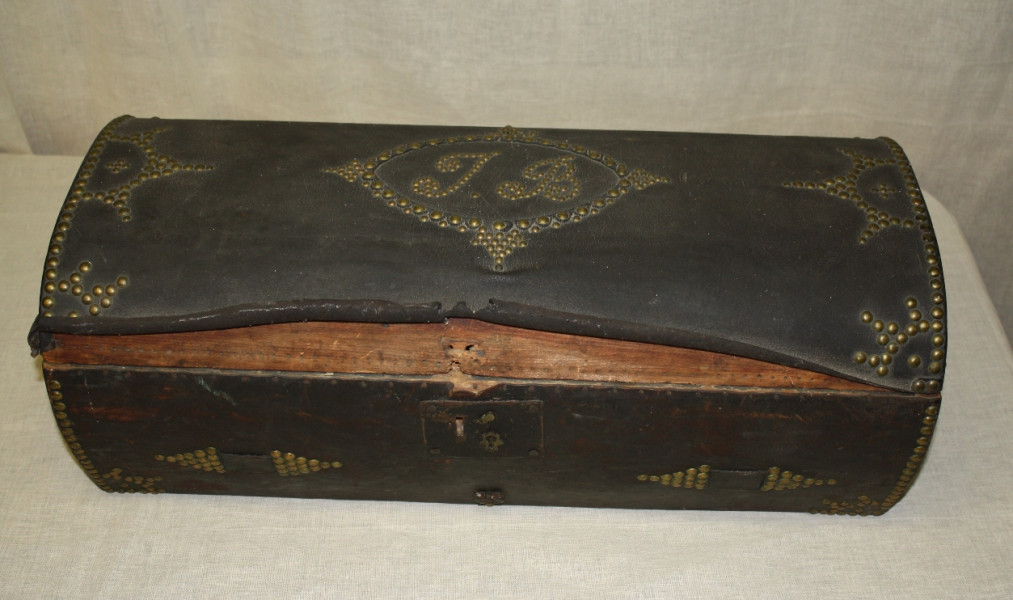

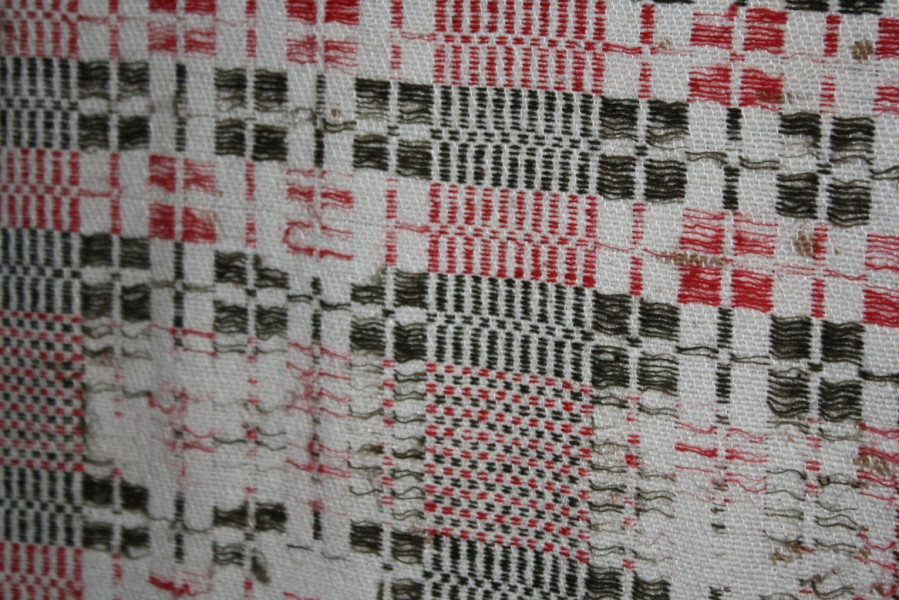

The American Loyalists who came to Missisquoi County not only brought their traditions and customs, language, religious beliefs, skills and ambitions, they also brought with them many items deemed necessary for survival. Often limited to what they could pack into a wagon or carry on their backs, it is fascinating to discover what these early settlers regarded as essential for carving out a new existence and a new life.