The rise of the Patriote movement in the 1820s and 1830s was a crucial turning point in Quebec’s history. For Louis Joseph Papineau, the eloquent spokesman of the Parti Canadien who led the resistance to the unification of the Canadas, Lower Canada was a distinct and important territory to be preserved as a French and Roman Catholic home for its inhabitants.

With Papineau at the head of the Patriote movement, criticism of the English-speaking merchants who controlled the Legislative Assembly increased. In 1837, when Britain rejected the Patriote’s demand for control of provincial expenditures by the Assembly, Patriote leaders initiated a programme of public rallies. For a few weeks in the autumn, Patriotes controlled parts of the countryside near Montreal. British troops were called to restore order and many Patriotes were arrested while others fled to the Richelieu Valley or across the American border.

In the United States, the Patriotes were seen as political refugees. Many inhabited the border regions on either side of Lake Champlain. In northern Vermont, Patriote refugees lived at Alburg, Highgate Springs, Swanton, St. Albans and Burlington. Many communities in Vermont held meetings in December 1837 and January 1838 in support of these political refugees and their cause. Most certainly, weapons and money reinforced this moral support.

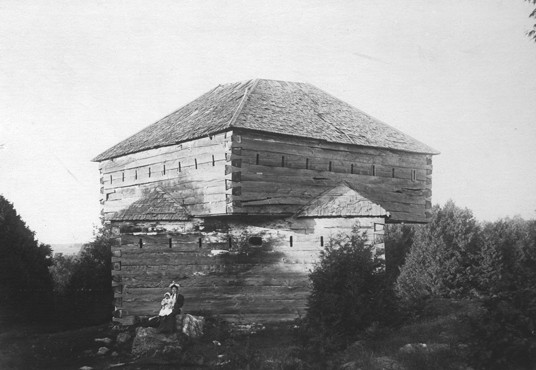

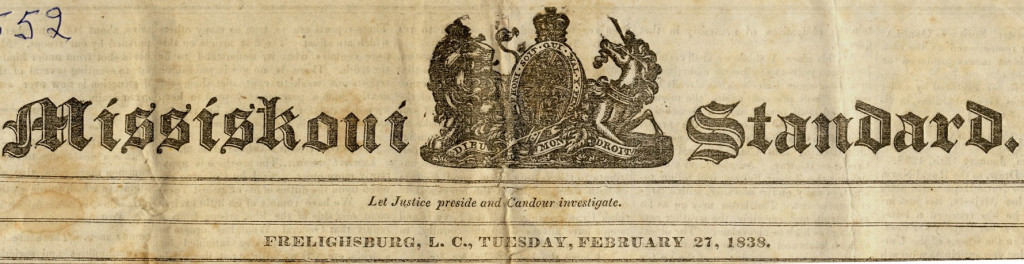

In Missisquoi County, a skirmish between 80 Patriotes and 300 Missisquoi volunteer militiamen occurred at Moore's Corner (St. Armand) on a cold December evening. At daybreak on December 6, 1837, an advanced guard of Patriotes disturbed the village of Philipsburg by damaging property and insulting citizens. Before departing, they boldly announced their plans to return later that day. True to their word, the Patriotes set out from Swanton, Vermont, equipped with two cannons and munitions. High with excitement and commitment to their cause, they did not realize they were marching into a well prepared and protected border region. Volunteers from Philipsburg, Pigeon Hill, Frelighsburg, Stanbridge East, Bedford and Mystic equally dedicated to protecting the border, met throughout the day in anticipation of an attack.

Severely outnumbered and out-maneuvered, the raid was a complete failure for the Patriotes. Panic stricken in the face of the fire-power that met them, they retreated across the border but not before one of their number was killed. The “Missisquoi Affair” reassured the government of Lower Canada that its armed supporters could be counted on even in the absence of troops.

References:

"The Moore's Corner Battle in 1837," in Missisquoi Historical Society Fourth Annual Report 1908-1909.

"The Rebellions of 1837 and 1838 in Lower Canada", Jean-Paul Bernard, Canadian Historical Association, 1996.