The first New England settlers arrived in what would become Eaton Corner in the late 18th century. There were no roads so they had to trek through the wilderness on foot, following old Indigenous trails and bringing with them only what they could carry on their backs.

Almost all were adult males, forerunners for their families. In the first few years they would return south for the winter. Their packs would include a few simple hand tools, such as axe, hammer and saw, some seed to plant their first crops, and a hunting musket which could also be used as a shotgun. Anything else they needed to survive, the homesteaders had to make by themselves.

Within a few years the newcomers were joined by their women and children. Meanwhile, a few blacksmiths were becoming the pioneer community’s first specialized workers.

Virtually everyone who could handle a knife was a part-time woodworker, making a range of products from rough spoons to fine furniture. But at the same time, they also had to be farmers, lumbermen, hunters, labourers, seamstresses, cooks, housekeepers, gardeners, nurses, parents, children and more. However, few of the settlers had the skills and knowledge to use a blacksmith’s forge for more than a fancy fireplace, so these things were usually made by the local smithy.

Virtually everyone who could handle a knife was a part-time woodworker, making a range of products from rough spoons to fine furniture. But at the same time, they also had to be farmers, lumbermen, hunters, labourers, seamstresses, cooks, housekeepers, gardeners, nurses, parents, children and more. However, few of the settlers had the skills and knowledge to use a blacksmith’s forge for more than a fancy fireplace, so these things were usually made by the local smithy.

Blacksmithing is an ancient trade, born of the Iron Age. The book Museum of Early American Tools, by Eric Sloane, has a good description:

“‘Smith’ from ‘smite’, ‘black’ from ‘black metal’ (as distinguished from silversmith brightwork), the blacksmith was the Early American handyman. He made nails, hinges, sled runners, anchors, scythes, hoes, utensils, axes, hooks, and every kind of tool. In the middle 1800s he began taking over the farrier's work of horseshoeing; till then the farrier was veterinary too. Blacksmith tool design has not changed very much except for the hazelwood withes that held all upper tools (chisels and swages). Hardly an implement or utensil cannot be traced to the early blacksmith.”

Using little more than fire, water, a hammer and a hard place, the ingenious village blacksmith provided an essential service, converting raw iron into anything one could imagine. In early Eaton Corner, every settler was a customer. Virtually everything the pioneers used was at least partly made of iron, from the kitchen, sitting room and bedroom to the river, farm and forest. There were no factories then, so everything was made by hand.

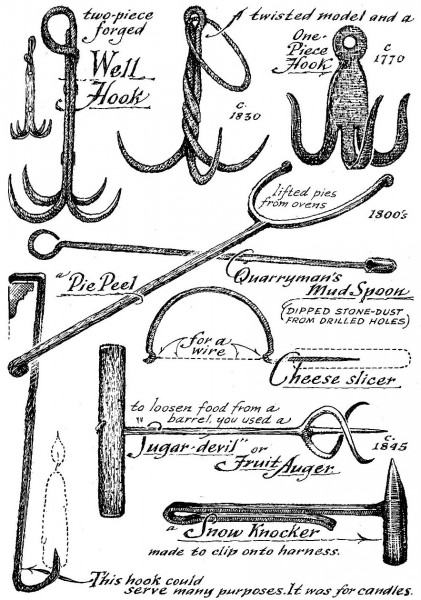

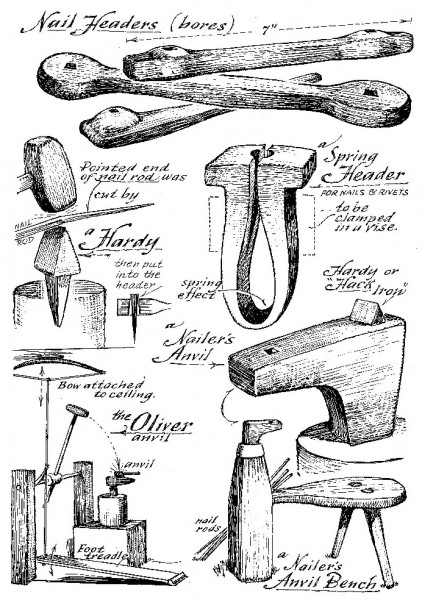

For the home, iron was made into equipment like hooks and hangers, braces and brackets, pots and pans for the hearth, until fireplace cooking was replaced by the stove in the second half of the 19th century.

For the home, iron was made into equipment like hooks and hangers, braces and brackets, pots and pans for the hearth, until fireplace cooking was replaced by the stove in the second half of the 19th century.

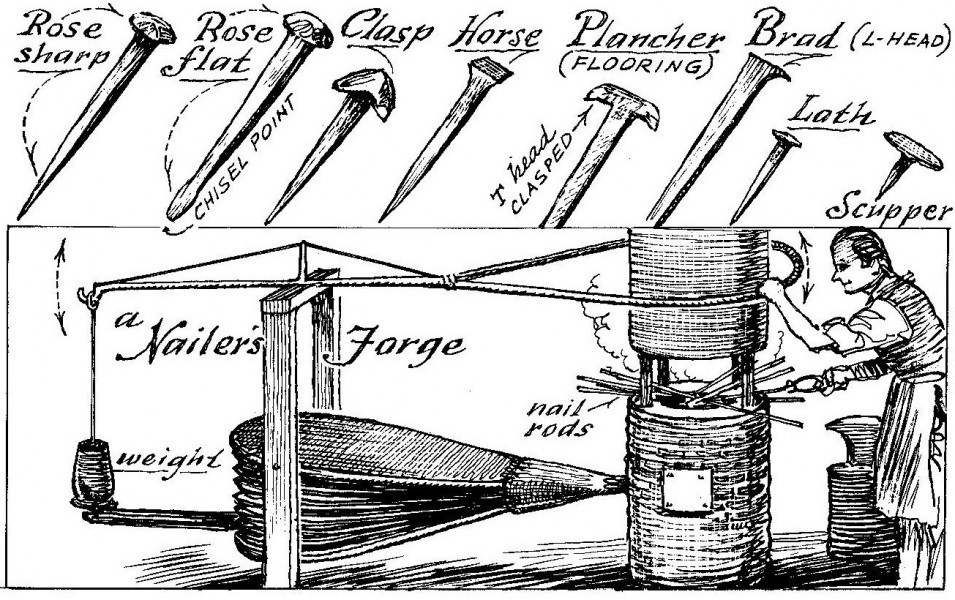

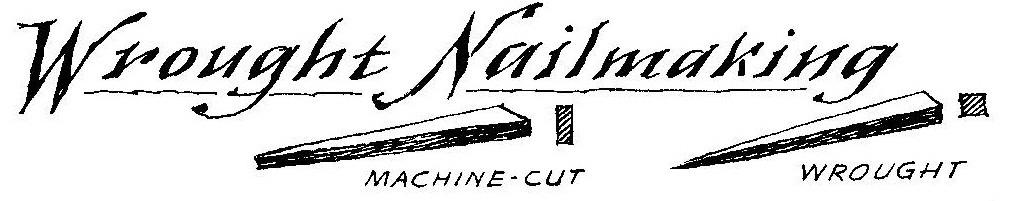

Kitchen and laundry utensils, clips, clamps and candlesticks, and household hardware such as hinges, latches, locks and keys were also made at the blacksmith shop. Iron nails held together just about everything from boxes and benches to the houses themselves.

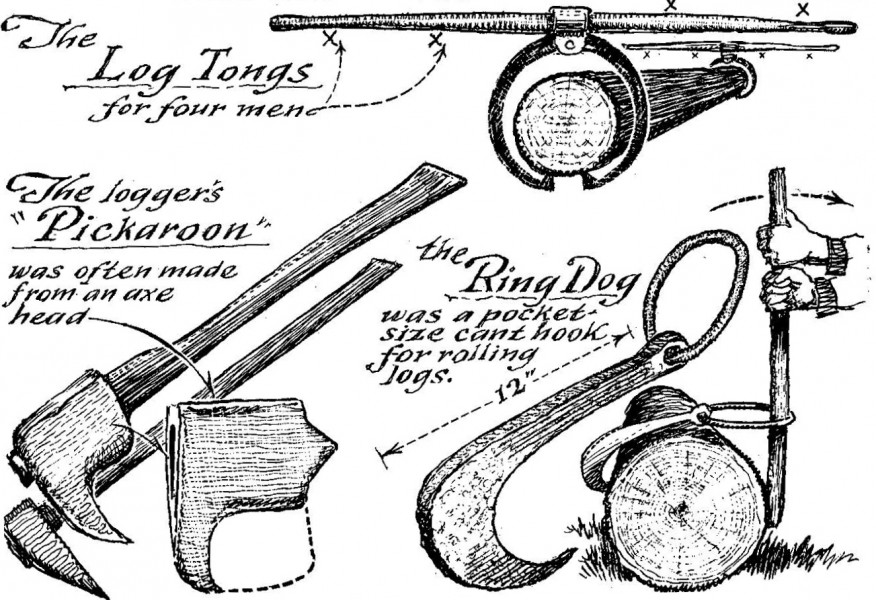

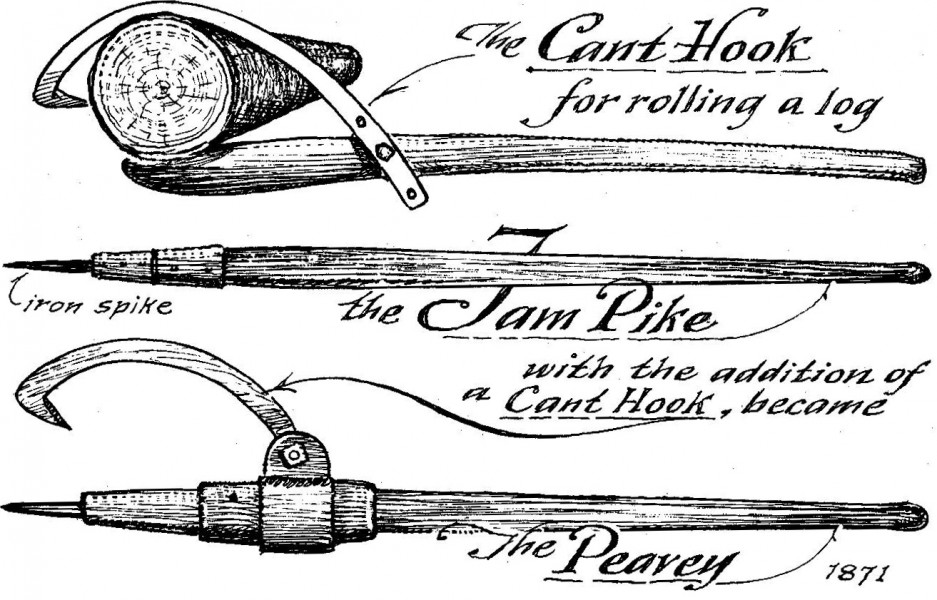

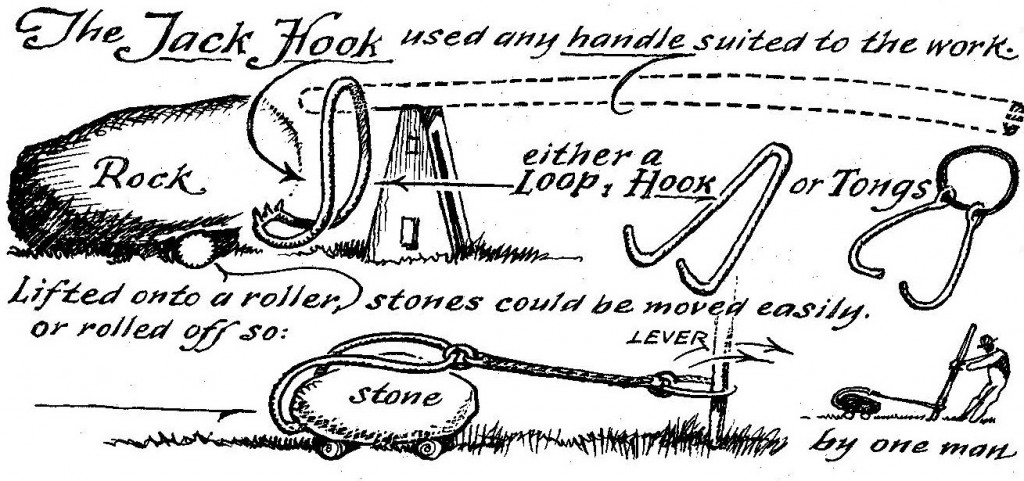

Outdoors, the pioneers’ tools consisted mainly of large pieces of wood, joined and strengthened with iron. Cutting, hauling, sawing and using lumber consisted almost entirely of wielding heavy wood-and-iron hand implements. Horse and cart were kept together by wood and leather attached with iron parts.

Every link of every chain had to be hammered into life in the fiery forge, while a hand-pumped bellows kept the fire hot. All day long, the blacksmith would hold iron parts with one hand and a hammer with the other to pound the parts into shape and harden them. As a result, veteran blacksmiths’ hammer arm, usually the right one, was much larger and more muscular than the other.

Every link of every chain had to be hammered into life in the fiery forge, while a hand-pumped bellows kept the fire hot. All day long, the blacksmith would hold iron parts with one hand and a hammer with the other to pound the parts into shape and harden them. As a result, veteran blacksmiths’ hammer arm, usually the right one, was much larger and more muscular than the other.

Until the village was big enough to support a carriage maker, the blacksmith’s shop was also the local garage, making and repairing carts, wagons, carriages, sleighs and sledges. The blacksmith was also called upon the create works of the iron maker’s art to adorn local buildings.

By about 1850 the demand for blacksmiths was far greater than New England could supply. As they did in many communities, French-Canadian blacksmiths – forgerons and ferronniers – became the first French-speaking residents of Eaton Corner.

Further reading:

The Canadian Encyclopedia online: www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com

La Confrérie des Forgerons du Québec: www.forgerons.qc.ca

New Hampshire Folklife: www.nh.gov/folklife

New England Blacksmiths: www.newenglandblacksmiths.org

Artist-Blacksmith's Association of North America: www.abana.org

Museum of Early American Tools, by Eric Sloane