In 1534 Jacques Cartier called it the land God gave to Cain. The French explorer couldn’t have dreamed that a string of towns would one day dot Quebec’s North Shore.

The Gulf of Saint Lawrence was a summer trading place for Indigenous tribes before European ships cruised its shores. When cod fleets, whalers and walrus hunters began venturing here in the early 1500s, crews found their metal tools fetched a fortune in furs. The profitable trade quickly grew from a sideline into a full-fledged industry.

Dearth of cropland made it a poor site for year-round settlement, however. Traditional home of the Montagnais Innu people, the North Shore east of the Saguenay River remained virtually unknown to colonists.

Innu missions, fishing stations, scattered trading posts and sawmills were the region’s only settlements until growth of the pulp-and-paper industry ended the North Shore’s isolation in the early 1900s.

English Quebecers share a part in this history. Their presence since the early 1800s has influenced the development of coastal communities between the ancient village of Tadoussac and the town of Port Cartier. This guide is an introduction to that heritage.

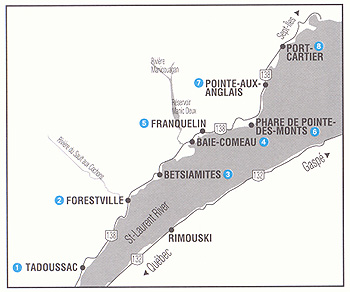

HOW TO GET THERE

Begin your tour at the head of the Saguenay Fjord, driving east from Quebec City on scenic Route 138. Or reach the North Shore by ferry from Trois-Pistoles, Rimouski or Matane on the South Shore and explore the coast in either direction.

TADOUSSAC (pop. 850)

By the mid-1800s Tadoussac had gained twin vocations as lumber settlement and holiday resort. Today the village is a busy tourist hub featuring historic landmarks, opportunites for whale-watching, a marine-mammal interpretation centre and a maritime museum.

In 1600 French fur trader Pierre Chauvin tried in vain to establish a colony here, a traditional bartering point for Iroquois and Algonquin peoples. At nearby Pointe-des-Alouettes in 1603 Samuel Champlain signed a pact with Algonquins against the Iroquois — the first treaty between Europeans and the Indigenous.

French success in the St. Lawrence roused the envy of London merchants. The celebrated English mariners, the Kirke brothers, seized Tadoussac in 1627; from its harbour they blocked French ships sent to relieve Champlain upriver at Quebec, seized by the English in 1629.

French success in the St. Lawrence roused the envy of London merchants. The celebrated English mariners, the Kirke brothers, seized Tadoussac in 1627; from its harbour they blocked French ships sent to relieve Champlain upriver at Quebec, seized by the English in 1629.

Restored to France by treaty in 1633, Tadoussac became the target of Iroquois attacks, the gravest coming in 1661 when the outpost was destroyed.

After France ceded Canada to Britain in 1763, English merchants ruled the Saguenay fur trade. First the North West Company then the Hudson’s Bay Company ran trading posts in Tadoussac from 1802 till 1860.

Quebec City wood merchant William Price began logging in the vicinity around 1840. Some of his descendants have kept homes in the community for generations. The simple white Tadoussac Protestant Chapel (1868) with its wood-plank siding and hardwood armchairs is a prominent landmark on rue des Pionniers.

The magnificent Hotel Tadoussac dates to the 1930s. It was the dream of W. H. Coverdale, head of Canada Steamship Lines from 1922 to 1949.

Other landmarks include the Chapel of Ste. Anne (1747), built on the site of an older Catholic chapel dating to 1647, and a replica of the original Chauvin habitation (1600).

North Shore Tourist Bureau

197 rue des Pionniers (418) 235-4744

Centre d'interprétation des mammifères marins

108 rue de la Cale Sèche (418) 235-4701

FORESTVILLE (pop. 3,900)

FORESTVILLE (pop. 3,900)

History records that a man named Jean Raymond was the first to clear trees near the mouth of the Sault-au-Cochon River in 1844. But it is an Irishman, William Grant Forrest, who is memorialized in the name of this village. Forrest was a longtime manager of local sawmill operations for the Price Bros. Company, which began operations here in 1848.

Most of the lumber cut at Forestville in the early years was destined for Britain’s naval yards. The settlement became a supply centre for area lumber camps until fire destroyed the Price mill in 1895.

The town was rebuilt in the 1930s by the Anglo-Canadian Pulp and Paper Co., looking to furnish its Quebec City newsprint mill. A long raised wooden trough that slid pulpwood from slasher mill to wharf on a stream of water was built at this time. It still hugs the shoreline. These flumes were a common feature of North Shore lumber towns before the highway was opened.

The Forestville Historical Society operates a summer museum in the old Trinity Anglican Church (1948) on 2nd Street.

La Petite Anglicane Museum

(418) 587-6148

BETSIAMITES (pop. 2,500)

BETSIAMITES (pop. 2,500)

This community at the mouth of the Bersimis River belongs to the Innu Nation whom early French explorers called Montagnais.

Betsiamites was a traditional gathering place for Montagnais Innu. Winters were spent far inland, hunting and trapping. Each summer they would move down river to spear salmon and eels, and to harpoon seals in the St. Lawrence.

A Hudson’s Bay Co. trading post was established just east of here at Ilets Jerémie, near the present-day village of Colombier. Indigenous trappers traded furs for lard, tea, butter, cloth and weapons.

Officially established as a reserve in 1861, Betsiamites was also a base for the Catholic Oblate religious order. Missionaries oversaw construction of the first chapel in 1854. The oldest surviving building in the village is the presbytery, which dates to the 1880s.

The Centre Villégiature de Papinachois is a summer visitor attraction featuring displays of traditional Indigenous culture.

Centre villégiature de Papinachois

418-567-8350

BAIE COMEAU (pop. 23,000)

BAIE COMEAU (pop. 23,000)

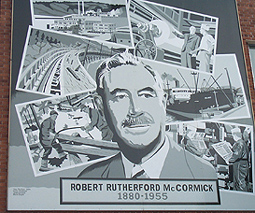

This resource-manufacturing town is rooted in a Depression-era deal between Quebec premier Louis Taschereau’s government and American newspaper tycoon, Col. Robert McCormick. The giant pulp-and-paper mill he built here in the 1930s still plays a vital role in the North Shore economy.

To furnish newsprint for his New York Daily News and Chicago Tribune newspapers, McCormick licensed rights to harvest thousands of acres of sprucewood in the Manicouagan River watershed.

The town’s small English colony was initially composed of mill managers who moved from McCormick’s plant in Thorold, Ontario. The houses they occupied in the vicinity of the Manoir Hotel today make up Baie Comeau’s historic district, bounded by Cartier, Champlain and Marquette streets.

Most of the town’s first residents were labourers and tradesmen drawn from French communities on the south shore of the St. Lawrence. Others hailed from Acadian settlements in the Gaspé and northern New Brunswick.

Most of the town’s first residents were labourers and tradesmen drawn from French communities on the south shore of the St. Lawrence. Others hailed from Acadian settlements in the Gaspé and northern New Brunswick.

Since the 1950s, an aluminum plant, grain-shipping port and numerous hydro-electric facilities have expanded Baie Comeau’s influence. Brian Mulroney, Canada’s prime minister from 1984 to 1993, was born here and lived on Champlain Street.

Though their numbers have declined sharply since the 1970s, a number of English Quebecers continue to make their home in Baie Comeau, including many descendants of the Quebec North Shore Paper Company’s original workforce. Baie Comeau High School across from the Ste-Amélie Catholic Church is the main hub of local English culture.

A heritage walking trail with interpretive panels begins at Parc des Pionniers. The Maison du Patrimoine, run by the Société Historique de la Cote Nord, houses a regional archives centre where visitors will find details on North Shore heritage, genealogical records and a guide to local sites of interest. Of special architectural interest is the Tudor-style Anglican Church of St. Andrew and St. George at 34 Carleton Ave., built in 1937.

Societe historique de la cote nord

9, rue Marquette (418) 296-8228

Church of St. Andrew and St. George

(418) 296-2833

FRANQUELIN HERITAGE

FRANQUELIN HERITAGE

FOREST VILLAGE

Anticosti Island promoter William Eshbaugh pioneered logging operations at the mouth of the Franquelin River as early as 1918, but sold his business to Col. McCormick in 1920. A settlement was established to supply wood for the Chicago Tribune’s newsprint mill at Thorold, Ontario.

Life in an old-time North Shore logging community is recreated at Village Forestier d’Antan, a unique visitor attraction just ten-minutes’ drive from Baie Comeau.

Village Forestier d'Antan

27, rue des Érables (418) 296-3203

POINTE-DES-MONTS

Historic Lighthouse and Museum

Built in 1829, this beguiling round stone tower 4 km west of Baie Trinité is one of the oldest lighthouses in North America and the second oldest in all of Quebec.

Classified as an historic monument, the seven-storey tower today houses a summer museum devoted to North Shore maritime heritage. The history of navigation in the St. Lawrence and details on local shipwrecks are among the featured exhibits. The adjacent lighthouse-keeper’s house operates as a bed-and-breakfast.

Lighthouse Museum

Chemin du Vieux-Phare, Baie-Trinité (418) 939-2400

POINTE-DES-ANGLAIS

Musée Louis Langlois

In 1711, a fleet of 70 warships carrying 5,000 British soldiers from Boston under Admiral Hovenden Walker ran onto rocks in a storm near Ile aux Oeuf (Egg Island) en route to Quebec. Twelve ships and 1,100 lives were lost. Walker’s failed attack bought France time to build her Louisbourgh fortress. For many years the sandy coastline along this stretch of the North Shore was a treasure-hunter’s paradise.

The Louis Langlois summer museum offers an interesting photographic exhibit on the infamous wreck of the Walker armada.

Musée Louis Langlois

2088, rue Mgr. Labrie (418) 799-2262

PORT CARTIER (Pop. 6,000)

PORT CARTIER (Pop. 6,000)

This scenic community straddling a series of small islands at the mouth of the Rocky River (Rivière des Rochers) got its start in 1918 as Col. McCormick’s first North Shore pulpwood operation, which he named Shelter Bay. The Rocky River has since become a renowned sports-fishing venue.

Vestiges of the old cutting and barking mills stand on McCormick Island. They were powered by a small hydro-electric dam built in 1922, which also supplied the town’s electricity. The dam site now houses a salmon museum.

Logging was the town’s sole industry for 40 years and the company provided key public services as well as most of the jobs, including schools and the settlement’s first hospital (1942).

Growth surged in the 1960s with the arrival of the Quebec Cartier Mining Co. The town’s deep-sea port was built on the Rocky River’s east flank and a 200-mile rail line laid to link the town with iron-ore mines in the Fermont area. Newcomers included English-speaking staff from outside Quebec who settled in the fine homes on Rochelois Boulevard overlooking the gulf. A handful of English families remain.

This guide is presented by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network and is made possible by a grant from Economic Development Canada and the Department of Canadian Heritage. Space constraints preclude mention of all possible sites. Thanks to Stephen Kohner, Brian Rock and Danielle Daignard. For more information call the QAHN office at (819) 564-9595 or toll free within Quebec at 1 (877) 964-0409.![]()

![]()