Griffintown and Point St. Charles were Canada’s first industrial slums, home to Irish immigrants fleeing the potato famines and generations of their descendants.

Griffintown and Point St. Charles were Canada’s first industrial slums, home to Irish immigrants fleeing the potato famines and generations of their descendants.

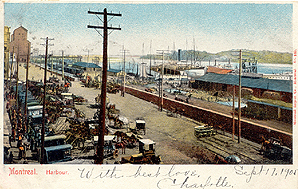

At the height of famine in the 1840s, as many as 30,000 Irish immigrants arrived in Montreal each year. Thousands died of typhus in fever sheds along the harbourfront. Some who survived the journey settled where they landed, on low-lying land at the edge of the St. Lawrence River. Here they laboured on the docks, in local foundries, brickworks, soap factories, breweries, flour mills and train yards.

This Heritage Trail walking tour leads to landmarks and points of interest in two of Montreal’s oldest working-class neighbourhoods, upon streets inhabited by builders of the Lachine Canal, the Grand Trunk Railway and the Victoria Bridge. St. Ann’s ward, which included Griffintown and the eastern part of Point St. Charles, furnished much of the brawn that fueled the city’s industrial growth in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Griffintown and “the Point” grew up round the hub of Montreal’s vast sea-to-rail shipping system. Where the harbour, the canal and the railway joined, Irish and French-Canadian families weaved their homes into proud and vibrant working-class communities.

Until the neighbourhood was partly bulldozed in the 1960s to build the Bonaventure Expressway, Griffintown was at the heart of Montreal’s Irish community. Point St. Charles’ mixed Irish, English, Scottish and French-Canadian inhabitants shared their neighbourhood with Ukrainians and Poles who emigrated to Quebec in the early 1900s.

The old factories along the canal are closed today. In the 1960s and 1970s, Griffintown landlords demolished many of the original workers’ rowhouses after the area was rezoned, forcing long-time tenants to move away. A number of historic sites and buildings survive, however, and it takes only a little effort to conjure up a sense of the past while strolling through the streets.

GETTING THERE

Start your exploration of old Griffintown and Point St. Charles at the Victoria Square metro station, at the western edge of Old Montreal. Go south along Victoria Square and turn left on McGill Street.

MCGILL STREET

McGill Street is the boundary between Old Montreal and Griffintown. The city’s western wall, torn down between 1804 and 1817, was located here, adjacent to the Old Port. Outside the wall lay one of the city’s oldest suburbs, a former seigneurial property owned by the Hotel-Dieu nuns and leased for farming. The area was variously known as the Nazareth fief and the Récollets suburb before 1804, when Mary Griffin, wife of a soap-factory owner, acquired the lease and set about to subdivide the land and plan streets. Irish immigrants began to settle in Griffintown around 1815. From 1821 to 1825, labourers from Griffintown were employed in the digging of the Lachine Canal.

GRAND TRUNK RAILWAY BUILDING

360 rue McGill

The Grand Trunk Railway spared no expense to build this opulent head office building, inaugurated in 1902. Incorporated in 1852, the Grand Trunk had an enormous impact on Canada’s development, undertaking construction of the country’s first main railway line the “trunk” from which all branch lines were expected to spring.

Operations of the Grand Trunk also shaped the growth of Point St. Charles. In 1861, the Grand Trunk was Montreal¹s largest industrial employer. A third of the company’s manufacturing jobs were located in the Point. The building belongs to the Quebec government today. Ask if the doorman will let you in to admire the impressive marble staircase with its cast iron railings rising toward a skylight.

Now continue along McGill., past Place d’Youville to rue d’Youville, and turn left.

ALLAN BUILDING

4 rue d’Youville

The Allan building (1858) housed the offices of the Montreal Ocean Steamship Company, belonging to Hugh Allan, a Scottish-born businessman once considered the richest man in Canada. A mark on the Allan building commemorates the springtime flood of 1886, one of the worst of the late 19th century. The flood was particularly disastrous for Griffintown and Point St. Charles as well as Old Montreal.

JOE BEEF’S TAVERN

201-207 rue de la Commune

Charles McKiernan, born in Ireland, was given the nickname Joe Beef during his years as quartermaster for the British Army during the Crimean War. He ran his famous waterfront tavern in this building from 1870 till his death in 1889. The tavern was well known to sailors and tramps, a source of food and shelter for the down-and-out. Joe Beef was famous for helping striking workers by providing bread and soup. He supported Lachine Canal workers during the strikes of 1877 and workers on strike at the east-end Hudon textile factory in 1882.

Joe Beef was also famous for keeping a menagerie of wild animals in the basement. Mention is made of four black bears, ten monkeys, three wild cats, a porcupine and an alligator. Apparently he sometimes brought a bear up from the basement to restore order when patrons got too unruly.

Now return to the Allan Building, cross rue de la Commune and the railway tracks and follow the riverfront to the railway bridge. The middle of the bridge marks the entrance to the historic Lachine Canal.

LACHINE CANAL

Twelve kilometres in length, the canal extends west from Old Montreal to Lachine. Inaugurated in 1825, it allowed ships to bypass the turbulent Lachine rapids in the St. Lawrence and continue upriver towards the Great Lakes.

The Lachine Canal was a crucial element in Montreal’s economic growth. Montreal's Anglo-Protestant industrialists were determined to preserve the city’s advantage as a transportation hub in competition with New York, whose access to the Great Lakes area was guaranteed by the Erie Canal. The canal was widened in the 1840s under conditions of bitter conflict between contractors and Irish labourers. Working 16 hours a day for low wages, labourers were paid in company scrip that could only be exchanged in company stores. A particularly violent strike took place in 1843.

Once widened, the canal was a source of hydraulic energy for Montreal’s early factories. By 1850, the canal was Montreal’s core industrial area. The canal was widened again by Irish workers between 1873 and 1885, again with strikes and labour unrest. In the second half of the 19th century, Montreal’s business élite continued to invest in transportation infrastructure, ensuring the city’s industrial and commercial preeminence. By the early 20th century, the canal was part of a network that included the Grand Trunk Railway, the Victoria Bridge, and modern harbour facilities.

The opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959 made the old canal redundant and factories began to close. The canal was filled in at the harbour entrance in the early 1960s and closed at the Lachine end in 1970. It remained closed for over 30 years as the southwest went through a period of economic decline. In 2002, the canal reopened for pleasure boating.

Follow the railway tracks alongside Grain Elevator No. 5 and come out near Mill Street. Cross the bridge to the north side of the canal and jog left along rue de la Commune to Prince Street. You are now in Griffintown. Follow Prince north to Ottawa Street and turn left.

DARLING BROTHERS FOUNDRY (circa 1918)

745 rue Ottawa

This is the second foundry built by the Darling Brothers. The first one, located east of here, was built in 1889. The company was very successful from the start and went on adding buildings over the years, including a third foundry, now demolished. Between 1851 and 1890, the number of foundries in Griffintown went from 8 to 20. The Darling Foundry closed its doors in 1991; it’s now an art gallery and restaurant.

Turning left on Ottawa Street, proceed under the Bonaventure Expressway and the railway bridge (1933).

NEW CITY GAS (circa 1859)

956 rue Ottawa, corner Dalhousie

Built in 1859, this is one of Montreal’s oldest surviving factory buildings. The New City Gas Company burned coke to produce gas, which was used to light Montreal’s streets, before the advent of electricity.

GRIFFINTOWN HORSE PALACE

1220 - 1224 rue Ottawa

The buildings and yard at 1220 - 1224 Ottawa Street house one of the last remaining stables in central Montreal. The Griffintown Horse Palace has been an Irish-owned stable since the 1860s. Today, the stable takes care of horses that pull tourist calèches in Old Montreal.

ST. ANN’S DAY NURSERY (1914)

287 Eleanor

From the corner of Ottawa and Eleanor streets, this elegant brick and terracotta-tile building stands out. It was once the Day Nursery of St. Ann’s Kindergarten, run by the Sisters of Providence. Today the building is occupied by King’s Transfer Van Lines, a moving company started by Griffintowner William O’Donnell in 1926. The business is now run by his grandson as part of Atlas Van Lines.

Turn left and head south on rue Montagne until you come to a park, the site of Griffintown’s historic parish church.

ST. ANN’S CHURCH

Historic Site

St. Ann’s Church was the heart of Griffintown’s Irish Catholic community. Built in 1854, it was Montreal’s second English Catholic church after St. Patrick’s (1847). Whereas the “lace-curtain” Irish around St. Patrick’s consisted of merchants, skilled workers and professionals, St. Ann’s parishioners were known as “shanty Irish” -- unskilled labourers employed in factories, in construction or on the docks.

The population of Griffintown began declining after World War II and in the early 1960s the city decided that Griffintown no longer had a future as a place for people to live. It was zoned as an industrial area in 1963. Then in 1967, part of the neighbourhood was demolished to make way for the Bonaventure Expressway. Having lost most of its parishioners, St. Ann’s church was torn down in 1970. The site of the church is a park today.

Turn right on Wellington Street and cross Wellington Bridge into Point St. Charles. Like Griffintown, Point St. Charles was once more densely populated than it is today. In the early 20th century its main drag was a bustling, animated street with a market, taverns, hotels, banks and stores. It’s interesting to note that Wellington Street follows a French colonial road that once linked Old Montreal to Lachine. At the time of the Conquest in 1759, General Amherst and his British troops marched east along this route into the city.

BLACK ROCK

A short side trip down Bridge Street leads to a unique tribute to Montreal’s Irish legacy, the Black Rock monument. Stay on the east (left) side of the street and walk south toward the Victoria Bridge. The monument, an enormous piece of granite weighing 30 tons, stands just south of Mill Street, between two traffic lanes, surrounded by an iron fence decorated with shamrocks.

The Black Rock was lifted out of the river in 1859 by workers building the Victoria Bridge. The workers decided to make it into a memorial for the thousands of Irish immigrants who had died of typhus in 1847. The rock marks the site of a mass grave.

The epidemic was a frightening experience for the population of Montreal; some responded with great courage and compassion. Among the people who died caring for the sick were the mayor of Montreal, John Easton Mills, three Catholic priests from St. Patrick’s church, and many Grey Nuns.

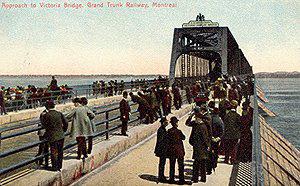

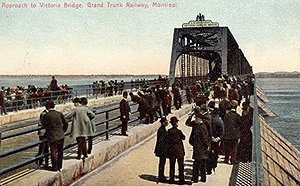

VICTORIA BRIDGE

VICTORIA BRIDGE

Inaugurated in 1860, the Victoria Bridge was the first bridge over the St. Lawrence in Montreal and a key element of Montreal’s modern transportation network. Before the bridge was built, the city’s economic activity slowed during winter months when the river was frozen. The bridge allowed trains to carry goods to Portland, Maine, an ice-free harbour from which they could be shipped to Europe. The bridge was a colossal project involving over 3,000 workers in 1858. The British company responsible for building the bridge brought over skilled workers from Great Britain. Brute labour was provided by Irish from Griffintown and the Point, and Mohawk workers from Kahnawake. Some of the workers were housed in empty fever sheds.

VICTORIATOWN

Around 1862, the immigrant sheds were torn down and houses built on land that now serves as a parking lot. By the 1890s, a tiny neighbourhood had sprung up at the foot of the Victoria Bridge, known as Victoriatown or Goose Village. This was a predominantly English-speaking neighbourhood at first. By the 1960s, though, half the residents spoke Italian. Victoriatown was bulldozed in 1963 in preparation for Expo 67. Return to Wellington Street and turn left.

GRAND TRUNK RAILWAY YARDS

West of Bridge Street, on the south side of Wellington, lies the site of the Grand Trunk Railroad’s former train shops, built in 1854-56. This was a colossal industrial complex, the largest in Montreal at the time. At first the workshops were designed to repair locomotives and railway cars. Later, new rolling stock was manufactured here.

In 1880, Grand Trunk employees worked an average of 9 to 10 hours a day on weekdays and 4 to 5 hours on Saturday, for a total of 52 to 54 hours a week. These would have been considered good conditions at the time. In many factories, workers worked 14 hours a day, 6 days a week. Visitors can glimpse Wellington Street’s glory years in the architecture of the old hotel at 1691 Wellington and the former Royal Bank of Canada building on the southwest corner of Wellington and rue Sainte-Madeleine, built in 1901.

Head south (left) on rue Congrégation and cross the little park diagonally to reach Sébastopol Street. This little park was the site of St. Matthew’s Presbyterian Church from 1858 to 1890. Turn right and head south on rue Sébastopol.

SÉBASTOPOL ROW

422-444 rue Sebastopol

These red and white stucco-clad houses are some of Montreal’s oldest surviving working-class housing, built in 1856. The area was known as Grand Trunk Row until 1882, when it was renamed to commemorate a British and French victory over the Russians in the Crimean War. The houses were built by the Grand Trunk to accommodate skilled workers brought from Great Britain to work in the Point St. Charles railway yards. The stucco was applied by an architect who bought the houses in the 1990s, hiding the original red brick.

Sébastopol Row is one of only two known examples of company housing in Montreal. The architecture of Sébastopol Row is thought to have been a key influence on the development of Montreal’s characteristic working-class housing in the 1860s and 1870s. Go right on rue Le Ber and right again on rue Congrégation till you reach rue Favard. Turn left and continue to rue Charon; then right on Charon and left on Wellington.

POINT ST. CHARLES ENGLISH COMMUNITY

Montrealers of English and Scottish origin also worked in the Point’s factories, sometimes as unskilled workers, more often as semiskilled workers, skilled workers or managers. Traces of the Point’s historic Anglo-Protestant community can still be seen along this stretch of Wellington Street: Grace Anglican Church, built in 1891 on the corner of Wellington and Ash streets; the middle-class Victorian row houses at 2131 - 2177 rue Wellington; and the former Baptist Church, now a Sikh temple, at 2183 rue Wellington.

Marguerite-Bourgeoys Park, on the corner of Wellington and Liverpool streets, would be a nice place to sit and eat a lunch before continuing your tour by heading north on Liverpool Street.

OLD KNOX FARM

The long row of working-class duplexes on the west side of Liverpool Street, beginning at number 636, was built in the late 19th century on land once owned by Irish farmer Robert Knox. The houses formed part of a larger neighbourhood originally populated by Irish, English, Scottish and French Canadian families. Many of the streets in the Knox Farm neighbourhood such as Coleraine, Ryde, Rozel and Rushbrooke honour Irish place names. Nobody refers to the area as Knox Farm today.

Now, turn left (west) on Coleraine Street then right (north) on Hibernia Street to continue our tour.

ST. GABRIEL FIRE STATION (1891)

A coat of arms designed in 1833 for the City of Montreal decorates the front of this building. It features symbols of Montreal’s four main population groups in the mid-19th century: a rose for the English, thistle for the Scots, shamrock for the Irish and a beaver for the French Canadians.

Go left (west) on Grand Trunk Street.

ST. COLUMBA HOUSE (1926)

2365 rue Grand-Trunk

St. Columba House is a community centre that has been a key institution in the Point ever since it was established by the United Church in 1926.

Turn right and walk north on Ropery Street, then veer right on Centre Street, leading past three historic Catholic school buildings which have served English-speaking students in the past.

St. Gabriel’s School (1886) stands on the corner of Ropery and Centre streets; École St-Jean l’Évangeliste (1883) at 2325 Centre St; and St. Gabriel’s Academy (1906) at 2312 Centre St.

ST. GABRIEL’S CHURCH (1895)

St. Gabriel’s was the second Irish Catholic church built in Point St. Charles, erected on the site of an older church dating to 1875. As is almost always the case in Montreal, Irish and French-Canadian Catholics, despite their geographic and social proximity, have separate parishes. In 1875, the Irish outnumbered French Canadians in Point St. Charles and for a short time St. Gabriel’s served both linguistic groups. But in 1883 a French Canadian parish was formed and a small wooden church built. The massive Église Saint-Charles next door to St. Gabriel’s was built in 1913.

Every year on the last Sunday in May, a procession of parishioners from St. Gabriel’s visits the Black Rock. Organized by the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the event commemorates the tragedy of 1847.

NORTHERN ELECTRIC BUILDING

Turn left on Shearer Street to see this enormous factory building, built in 1913 and enlarged in the 1930s. Northern Electric was one of the largest employers in Point St. Charles with 9,000 workers in 1940. The building occupies a large area previously occupied by a basin and a sawmill.

A left turn onto St. Patrick Street leads west to another industrial landmark.

BELDING CORTICELLI FACTORY (1884)

Corner St. Patrick St. and rue Des Seigneurs

Originally known as the Belding Paul, this was the first silk factory in Canada, built in 1884 to produce silk ribbons. During World War II factory workers turned out nylon stockings.

A right turn onto rue Des Seigneurs leads north over the historic Des Seigneurs Bridge, site of Montreal’s first large mill operations. Pause on the bridge.

ST. GABRIEL LOCK

After the Lachine Canal was widened in the 1840s, the increased water power at this lock became a valuable energy source. St. Gabriel Lock powered some of the oldest factories in Montreal.

The land on both sides of the canal had formerly been a farm belonging to the Sulpician priests. In 1840, the government required the religious order to subdivide the land and sell it for industrial development. Some of the most valuable lots were acquired by John Ostell, architect of St. Ann’s Church and the New City Gas Company, who sold them at a considerable profit in the early 1850s.

REDPATH SUGAR REFINERY

Looking east from the middle of the Des Seigneurs Bridge, notice a tall red brick building rising to the east of the Belding-Corticelli factory. The Redpath Sugar Refinery, built in 1854, was the first sugar refinery in Canada and one of the first factories at St. Gabriel Lock. It was founded by John Redpath, a Scottish-born entrepreneur who had been involved in building the Lachine Canal and many other works. The refinery closed in 1979.

OGILVIE FLOUR MILL (1837-1915)

Continue across the bridge to the north side of the canal, where the remains of the Ogilivie Flour Mill have been under investigation by archaeologists since 2002. Built in 1837, the mill was the first industrial establishment on the banks of the canal; it was enlarged in 1851 to take advantage of the hydraulic power provided by the recently widened canal. The five-storey building was demolished in 1915.

Return across the bridge to the south side of the canal, and walk west along the canal to rue Charlevoix. To reach the Charlevoix metro station, walk south on rue Charlevoix to the corner of Centre St.

![]()

![]()