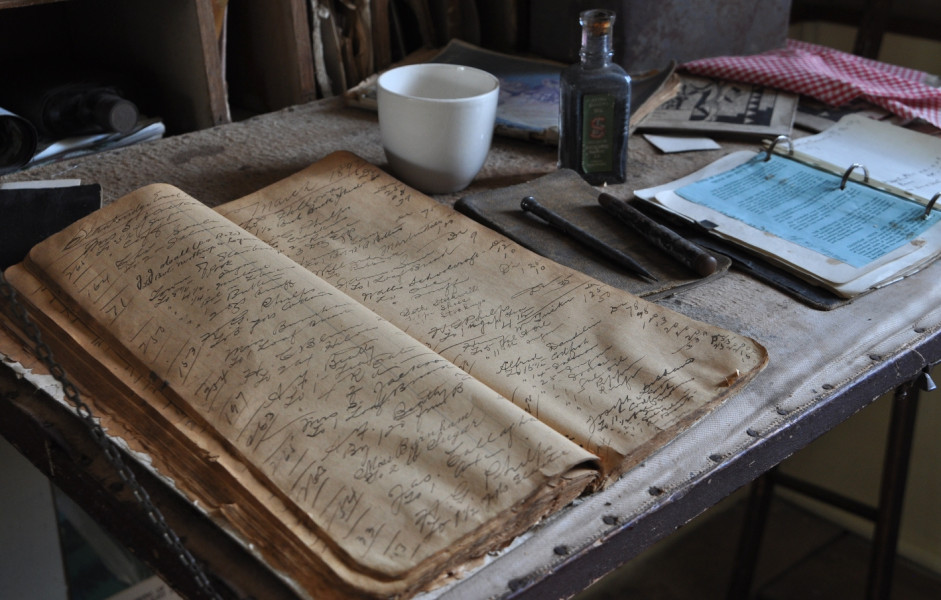

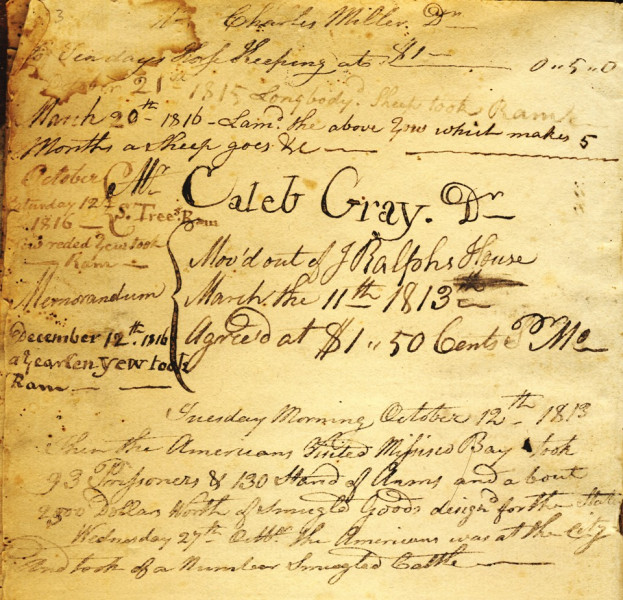

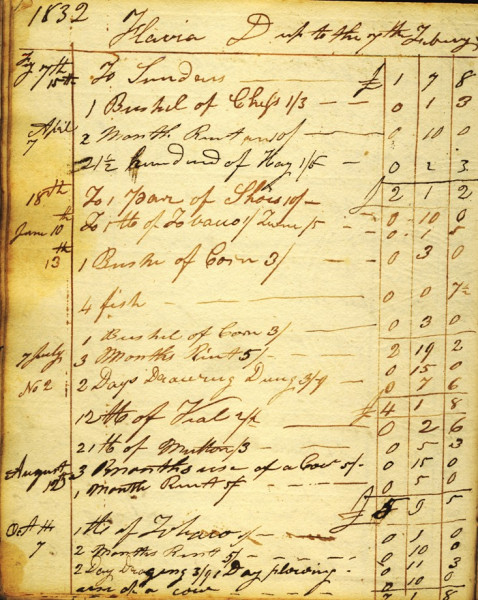

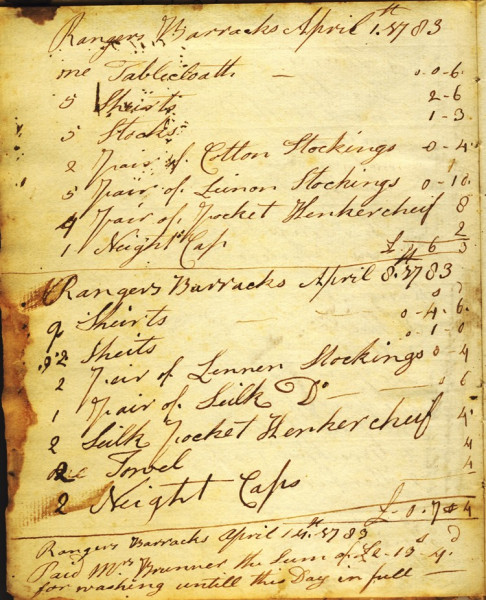

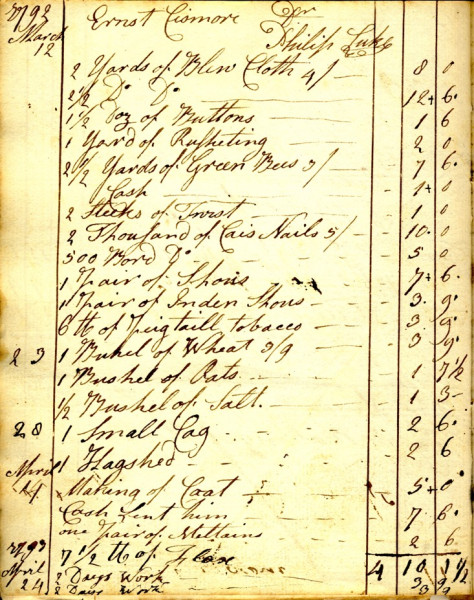

Business account books or ledgers from the 19th and early twentieth centuries are a valuable resource for the study of rural history. Historians have used account books to reveal their subjects’ community through the markets they operated in, the people they dealt with, and the goods they produced and consumed. The time that went into creating these ledgers reveals the importance of the daily relationships they recorded.

The accuracy of the ledgers and the success of the early stores depended entirely on the probity of the merchant who operated the business and whose steady hand recorded the daily hustle and bustle in his store. That attention to detail in many of the Missisquoi County ledgers now offers the researcher a unique picture of the social life and the exchanges of commodities in this newly populated area of the Eastern Townships.

The stores that succeeded in business in Missisquoi tended to be headed by men who were seen as honest leaders of the community. Their general stores served not only as places to purchase goods but also as banks and places to conduct business and settle disputes. In addition, and in particular to the Philip Luke and Philip Ruiter establishments, storekeepers also found urban markets for their customers’ surplus produce and acted as intermediaries between the urban markets of St. John’s and Montreal and the citizens of Missisquoi Bay. Both Luke and Ruiter operated boats to transport goods to the larger markets.

It was imperative then that the store owner was a person of integrity, since he was dealing with goods, services and money belonging to his neighbours.

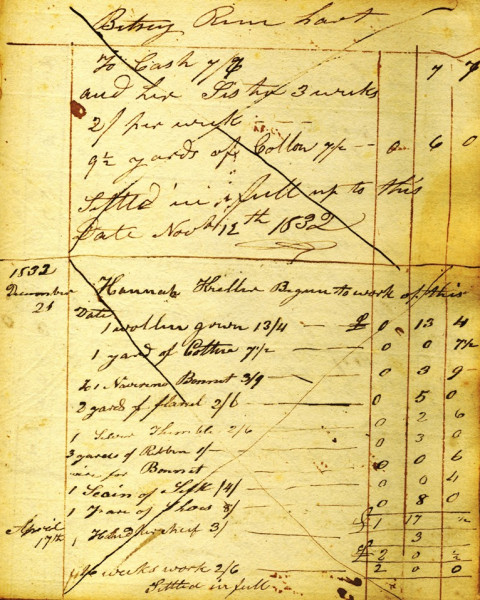

The ledgers of Philip Ruiter and Philip Luke, from the early community known as “Missiskoui Bay” (Philipsburg), bring to light the relative prosperity and indebtedness of the community and the careful manner in which each man conducted his business. Some customers made frequent purchases and yet never paid directly, choosing instead to settle accounts sporadically throughout the year. Others always paid their bills in cash at the time of purchase, and still others carried over their debts month after month and hoped for better times. Keeping track of the transactions required a merchant to be skilled in accounting and organized in his daily transactions.

The ledgers of Philip Ruiter and Philip Luke, from the early community known as “Missiskoui Bay” (Philipsburg), bring to light the relative prosperity and indebtedness of the community and the careful manner in which each man conducted his business. Some customers made frequent purchases and yet never paid directly, choosing instead to settle accounts sporadically throughout the year. Others always paid their bills in cash at the time of purchase, and still others carried over their debts month after month and hoped for better times. Keeping track of the transactions required a merchant to be skilled in accounting and organized in his daily transactions.

The ledgers of Missisquoi County illustrate how people paid their bills and received remuneration for their labour, as well as their level of indebtedness to a store, the frequency of their purchases, and their shopping patterns. A customer’s good relationship with the store owner was necessary for basic survival in this new region of settlement. If one was in good standing, then the store owner was apt to be more lenient in demanding the payment of debts and more inclined to accept payment in kind or in labour rather than insist upon payment in currency.

Similarly, if a store owner had a reputation for being fair and for offering quality merchandise at fair market value, he was likely to prosper in business. As revealed in their ledgers, both Philip Ruiter and Philip Luke left behind a legacy of their good and honest work.

This exhibit presents an overview of the important early store ledgers that are now in the possession of the Missisquoi Historical Society, as well as some of the many types of consumer goods that would have been purchased in Missisquoi County -- at establishments such as Hodge’s General Store, in Stanbridge East, which is now a part of the Missisquoi Museum.

References:

The Philip Ruiter Ledgers (courtesy of Phyllis Montgomery & Robert Galbraith); The Philip Luke Ledger, Missisquoi Historical Society Collection; G. H. Montgomery, “Missisquoi Bay” (Philipsburg, Que. 1950).