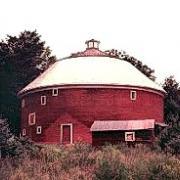

Round barns were at one time scattered all across the southern part of the Eastern Townships. In fact, in Quebec, they were almost totally confined to this region. Unfortunately there are only a handful left. Dating in most cases to the early 20th century, they represent an important part of our architectural heritage.

Round barns were at one time scattered all across the southern part of the Eastern Townships. In fact, in Quebec, they were almost totally confined to this region. Unfortunately there are only a handful left. Dating in most cases to the early 20th century, they represent an important part of our architectural heritage.

The curious circular form of the round barn is the subject of much superstition. Like the X-shaped marks (hexes) that many farmers traditionally painted on their barn doors, round barns are connected in popular folklore with the notion of making the devil feel unwelcome. A hex mark was meant to frighten off the devil, who, if he entered the barn, was apt to hide in any number of dark corners, causing mischief, setting fire to hay, and other such things. In a round barn, however, there were no corners for him to hide in.

Other proponents of round barns held that the circle was the perfect shape. In architecture, it was believed, a round shape promoted health, happiness, and better motivation in work. Some of these beliefs, particularly the one about the devil hiding in corners, may have originated with the Shakers, a religious group that erected the first round barns in New England in the 1820s. Round barns, like much of our early domestic architecture, covered bridges, and even popular beliefs and superstitions, were imported from New England. In Vermont, there are still about a dozen round barns standing.

Notwithstanding the folklore, the motives for constructing round barns in the Eastern Townships were infinitely more practical, and had to do with economy and efficiency. Specifically, the circular shape offered farmers a more efficient organization of space within the barn. Cattle, which were kept on the ground floor, could be oriented towards the centre, facilitating both feeding and cleaning. The upper floor, as in rectangular barns, was used for storing feed and implements. There were other advantages. With windows all around the building, a constant supply of light was assured at all times of day. Ventilation was said to be better. Also, the aerodynamic shape minimized the force of violent winds. Finally, a round barn was no more difficult to build than a traditional barn, but it used less wood in the structure.

There were serious disadvantages, however. The circular shape required many more and shorter pieces of wood for the siding. More important, it was nearly impossible to expand the barn by adding other buildings. Ultimately, it was technological change in 20th century dairy farming (improved piping, and so on) that spelt the end of the round barn in the Eastern Townships. Indeed, the fad was over almost as soon as it had begun.

There were serious disadvantages, however. The circular shape required many more and shorter pieces of wood for the siding. More important, it was nearly impossible to expand the barn by adding other buildings. Ultimately, it was technological change in 20th century dairy farming (improved piping, and so on) that spelt the end of the round barn in the Eastern Townships. Indeed, the fad was over almost as soon as it had begun.

Today there are nine round barns still standing in the Eastern Townships. All are located relatively close to the American border. The largest concentration is in the Coaticook MRC (including two in the vicinity of Way's Mills, one in Barnston, and one built in 1995 in the Gorge de Coaticook Park). Other examples may be found in Mansonville, Saint-Benoit-du-Lac (a round barn and a round hay tower), one in West Brome, one near Dunham, and a unique 12-sided one in Mystic. A number of these barns are in very poor condition. Two others in the Coaticook MRC have collapsed in recent years.