Missisquoi Bay on Lake Champlain was a haven for refugees during the American Revolution. In the 1770s and 1780s, they came by the thousands into Quebec, mainly from New York’s upper Hudson and Mohawk river valleys.

These migrants reached British soil near a traditional Abenaki village on the mouth of the Missisquoi River, the district then forming a largely unpopulated seigneury called St. Armand.

Many of these frontiersmen were Loyalist soldiers whose properties were seized during the war and who were expelled from the new United States. As compensation, they asked Canada’s colonial government to grant them title to lands north of the border.

The American exodus continued northward along the Richelieu and St. Lawrence rivers, but a number of families stayed where they’d landed, clearing fields and putting down roots along the fertile shores of the bay.

Missisquoi settlers felled trees and shaped crude timber for their cabins with broad axes. They formed a core group of early pioneers who led the push to bring Quebec’s Eastern Townships under the plow.

As log cabins gave way to farmhouses, lonesome mill sites in Missisquoi County sprouted into bustling towns, attracting British and later, French Canadian colonists. This Trail leads to historic Townships settlements that proudly flaunt this blended heritage.

GETTING THERE

GETTING THERE

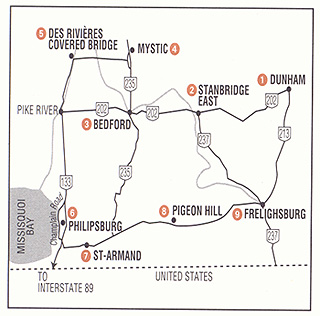

Visitors coming from New York or Vermont may wish to start the tour at Philipsburg just north of the border crossing on Interstate 89. If you are coming from Montreal, follow Autoroute 10 east, get off at St-Jean-sur-Richelieu, and take Route 133 south.

From Sherbrooke, follow Autoroute 10 west and exit onto Route 139, heading for Cowansville, then drive south on Route 202.

DUNHAM

(Pop. 3,344)

Thomas Dunn, seigneur of St. Armand and a senior colonial administrator in Lower Canada, gained title to Dunham Township along with 34 associates, in 1796. Dunham village developed as its social, commercial and administrative hub.

Dunham farmers were food-making innovators in Quebec. In 1865, the province’s first large-scale cheese factory opened here. Remains of this historic dairy plant stand 100 metres or so behind the municipal library on Maska Road.

For more than a century, Canadian and American maple-syrup producers relied on equipment made on Main Street by the Small Brothers company. In 1893, the Smalls, of Scottish descent, bought the patent owned by David Ingalls of East Dunham for an evaporating pan that shortened boiling times. They ran their business in the old Seeley Hotel, a former stagecoach stop on the road to St. Alban’s, Vermont. This tall red brick building with an arched coach entrance now furnishes space for restaurants and shops.

For more than a century, Canadian and American maple-syrup producers relied on equipment made on Main Street by the Small Brothers company. In 1893, the Smalls, of Scottish descent, bought the patent owned by David Ingalls of East Dunham for an evaporating pan that shortened boiling times. They ran their business in the old Seeley Hotel, a former stagecoach stop on the road to St. Alban’s, Vermont. This tall red brick building with an arched coach entrance now furnishes space for restaurants and shops.

An unusually mild local climate has earned Dunham fame more recently as the capital of Quebec’s wine industry.

Before it closed in 1972, Anglican school girls from across Canada knew Dunham as the home of St. Helen’s College, a private boarding school built in 1878. The Quebec Women’s Institute was founded in Dunham in 1911. A cairn on Main Street commemorates this event.

STANBRIDGE EAST

(Pop. 400)

First settled by New Englanders in 1801, Stanbridge East developed into a farming and industrial centre. By the 1830s, Stanbridge had a post office, bank, tannery, brick works, foundry and a grist mill.

Early settlers harnessed the Pike River to grind their cornmeal and buckwheat into flour. Today the Cornell Mill (1830) is home to the Missisquoi Museum, which contains one of Quebec’s best rural heritage and archival collections. The mill is part of a museum complex that includes Hodge’s Store and Bill’s Barn, where antique farm machinery is exhibited.

Early settlers harnessed the Pike River to grind their cornmeal and buckwheat into flour. Today the Cornell Mill (1830) is home to the Missisquoi Museum, which contains one of Quebec’s best rural heritage and archival collections. The mill is part of a museum complex that includes Hodge’s Store and Bill’s Barn, where antique farm machinery is exhibited.

The village was once a hotbed of rebellion. In the early 19th century, several villagers joined Louis-Joseph Papineau’s Patriotes in rejecting British control over Lower Canada’s parliament. In 1834, they founded the newspaper, The Missiskoui Post, to call for reform. British troops threw their printing press into the river during the 1837 Rebellion.

The range of architectural styles on display around the village common is strongly reminiscent of rural New England. The historical society has published a walking-tour guide to the village, available at the museum. It highlights more than thirty landmarks, including a former schoolhouse (circa 1820) at 13 Maple Street, where American president Chester Arthur’s father once taught.

Now return to Route 202 and follow signs for Bedford, the largest urban settlement along the Trail.

Missisquoi Historical Society and Museum

Tel.: (450) 248-3153

BEDFORD

(Pop. 2,750)

Bedford’s historic residential quarter features outstanding Victorian homes that tell of Bedford’s glory days as a railway and manufacturing hub. Turn onto Clayes Street off Route 202 (chemin de la Rivière) just before rue du Pont to explore this district, bounded by Dutch and Rix streets and Philipsburg Ave.

At the turn of the 20th Century, ninety per cent of Missisquoi residents claimed American or English heritage, and the homes and churches they built reflect the Anglo traditions of the period. Among Bedford’s early settlers was Abram Lampman, a German-American pioneer who built a dam and mills here.

Many heritage buildings can also be seen along rue Principale, including the Cyr Block (1894) which incorporates part of a much older meeting hall known as Victoria Hall.

Saint James Anglican Church (1832) on rue du Pont, famous for its stained glass windows, features the simple neoclassical style architecture favoured by many Loyalist builders in the region. It stands in contrast with the magnificence of Bedford’s St-Damien Catholic Church (1911), on rue de l’Église. Our Trail passes both churches as Route 235 leads across the bridge toward Mystic.

MYSTIC

MYSTIC

(Pop. 63)

Townships architectural heritage features a few round wooden barns, but the 12-sided barn in this hamlet is in a class by itself. Built in 1882 by a local inventor and manufacturer named Alexander Walbridge, the barn features a water-powered central rotating mechanism. Walbridge lived in Mystic from the 1860s till his death in 1897. His heirs have established a foundation to preserve this unique heritage site.

Take a moment to admire Mystic’s Model School, built by Walbridge in 1886 and crowned by a bell-tower. Walbridge also built the United Church and is buried in the adjacent cemetery. The Auberge l’Oeuf, an inn and restaurant at the corner of Walbridge and St-Charles range roads, occupies a former general store built in 1865 and renovated in 1920.

Once called Stanbridge Centre, Mystic was first settled around 1830. A mill was erected on the Pike River in 1836 by Benjamin Hauver, of German-loyalist stock. Now follow St-Charles Range Rd. over the railway tracks and out of the village for a brief drive through the countryside.

DES RIVIÈRES COVERED BRIDGE

DES RIVIÈRES COVERED BRIDGE

This historic bridge over the Pike River was built according to the William Howe patent and is part of a vanished pioneer settlement known as Des Rivières, seat of the former French Seigneury of Malmaison. The impressive manor house still stands behind a grove of pines just south of the bridge on chemin Des Rivières.

The original 31,000-acre estate once belonged to James McGill, founder of McGill University. It was passed on to the Des Rivières family upon his death in 1813. In 1842, Henri Des Rivières built a dam across the river here and opened two water-powered sawmills. One of these buildings still lies on the river’s east bank.

The first covered bridge at this point was built by Des Rivières in 1843, but it was swept away by a spring flood in 1883. The present structure was built to replace it in 1884.

Cross the bridge and turn left onto chemin Des Rivières, which leads to Route 133 near the village of Pike River. A tourist information kiosk is located in an old church presbytery on your left.

Now follow Route 133 south, veering right onto Champlain Road, which leads to Philipsburg on the shore of Missisquoi Bay.

PHILIPSBURG

(Pop. 245)

Many pioneer families first entered Quebec through this border settlement on Lake Champlain. Established in the early 1780s as a refugee camp for Loyalists, Philipsburg was the first real village to take shape in the St. Armand Seigneury.

Philipsburg became home to a number of New England families who later influenced the development of the Eastern Townships. These include Gilbert Hyatt, founder of the City of Sherbrooke.

Many Loyalists of German stock settled at Philipsburg, notably Christian Wehr, a leader of the Missisquoi colony. During the War of 1812-14, American colonel Isaac Clark landed a naval force of 400 men near the village, carrying off 100 local militiamen as prisoners.

The village boasts some of the oldest buildings in the Townships, including a square-log cabin built by Simon Lyster in 1784. The remodelled home stands at 22 Champlain Road. Philipsburg’s marble Methodist church (1819) is another major heritage attraction. During the 1837 Rebellion, local militia barricaded the German Palatine-style chapel and used it as an armoury. Later, it was plastered with mortar to protect its walls from Patriote bullets.

The village boasts some of the oldest buildings in the Townships, including a square-log cabin built by Simon Lyster in 1784. The remodelled home stands at 22 Champlain Road. Philipsburg’s marble Methodist church (1819) is another major heritage attraction. During the 1837 Rebellion, local militia barricaded the German Palatine-style chapel and used it as an armoury. Later, it was plastered with mortar to protect its walls from Patriote bullets.

During the 1860s, fugitive slaves from the American South found refuge in Philipsburg and St. Armand homes on their way to freedom in Canada, part of the famous Underground Railroad.

Visitors may wish to pay a visit to the Philipsburg Protestant Cemetery on South Road before continuing along the Trail.

ST. ARMAND

(Pop. 1202)

The last battle of the Rebellion of 1837 south of the St. Lawrence River was fought at this crossroads, also known as Moore’s Corner, on Dec. 6, 1837. Here a group of 80 Patriote rebels who had gathered at Swanton, Vermont, were intercepted and scattered by 300 Missisquoi volunteer militiamen.

Some of the Patriotes were captured after taking refuge in the old Hiram Moore place, a white house opposite town hall on the corner of Bradley and St. Armand roads. A plaque has been erected on the balcony of this building, classified as a historical site.

A little known pioneer cemetery at Nigger Rock is the resting place of the area’s early black population. Research continues on whether those buried here were escaped slaves from the south or servants who came here with Loyalist families. To view the cemetery make an appointment with the St-Armand Historical Centre.

A little known pioneer cemetery at Nigger Rock is the resting place of the area’s early black population. Research continues on whether those buried here were escaped slaves from the south or servants who came here with Loyalist families. To view the cemetery make an appointment with the St-Armand Historical Centre.

Centre Historique de St-Armand,

166 rue Quinn, St-Armand. Tel. : (450) 248-3393

PIGEON HILL

(Pop. 40)

Originally known as Sagerfield, this knoll-top hamlet offers fine examples of New England-style architecture as well as scenic views of Pinnacle Mountain, especially from the cemetery behind Saint James Church (1859). When early settlers arrived in the area, they found a ready food supply in the millions of passenger pigeons roosting on the hill.

Pigeon Hill was the site of a military battle on June 7, 1866 when Fenian raiders were repulsed by members of the Canadian Militia after plundering nearby Frelighsburg and St. Armand.

FRELIGHSBURG

(Pop.1078)

Few villages in southern Quebec can rival Frelighsburg’s mix of heritage buildings and pastoral charm. First settled by New Englanders who built a mill on the Pike River here around 1790, the village is famous for its 19th century American-style wood and stone dwellings.

The settlement takes its name from Abram Freligh, a doctor of Dutch descent from New York who bought the millsite in 1800. In 1839, his son Richard built a second, larger mill out of stone, which remained in use until 1964. The Freligh mill was classified a historic monument in 1973, and has since been restored by its owners.

The settlement takes its name from Abram Freligh, a doctor of Dutch descent from New York who bought the millsite in 1800. In 1839, his son Richard built a second, larger mill out of stone, which remained in use until 1964. The Freligh mill was classified a historic monument in 1973, and has since been restored by its owners.

In 1870, local militia called the Red Sashes repelled a second Fenian invasion at nearby Eccles Hill. A large cairn has been erected on the site about two kilometres from the village along Eccles Hill Road.

This guide is presented by the Quebec Anglophone Heritage Network. The Heritage Trail series is made possible by funding from the Department of Canadian Heritage and Economic Development Canada. Space constraints preclude mention of all possible sites. Thanks to Heather Darch, Pamela Realffe and Judy Antle of the Missisquoi Historical Society for their help. For more information call the QAHN office at (819) 564-9595, or toll free within Quebec at 1 (877) 964-0409.![]()

![]()